The climatic process was compared to an air conditioner operating at its limits.

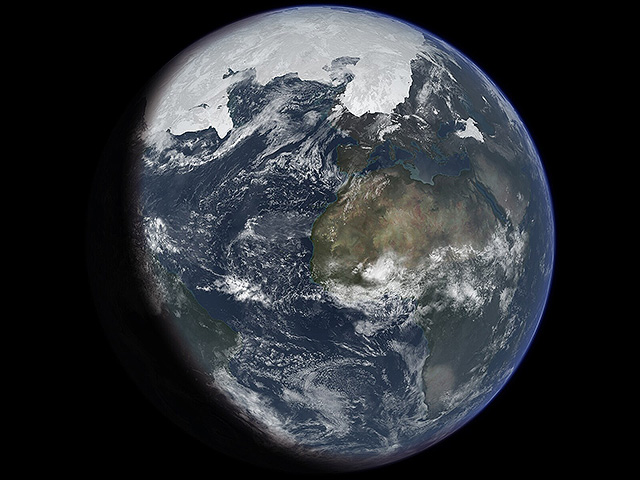

Scientists from the University of California have stated that they have discovered an important missing element in the classical representation of the carbon cycle on Earth. According to them, addressing this gap shows that phases of global warming can eventually 'morph' into the opposite extreme – a sharp cooling, potentially leading to conditions favorable for the onset of an ice age.

For a long time, it was believed that the planet's climate is balanced by a slow but steady natural mechanism related to the weathering of rocks. This process was considered a kind of climate regulator, preventing temperature from deviating too much in either the warming or cooling direction. The essence of the mechanism is that rainwater absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and, upon reaching land, reacts with rocks, primarily silicate ones like granite. As a result, the rocks gradually break down, and the dissolved substances along with CO₂ are carried to the ocean.

In the ocean, carbon binds with calcium, forming shells of marine organisms and limestone structures. Over time, these formations settle to the bottom, effectively 'locking' carbon in sedimentary rocks and thereby reducing its concentration in the atmosphere for geological epochs. However, data from the geological record indicate a more complex picture. Some ancient ice ages were so extreme that ice and snow covered nearly the entire surface of the planet. According to researchers, such radical glaciation poorly aligns with the idea of a smoothly self-regulating climate system.

This prompted the team to search for an additional mechanism capable of pushing the climate out of a stable state and leading it to sharp extremes. The identified factor is related to the processes of carbon burial in the ocean. As CO₂ concentration rises and temperatures increase, runoff from land washes more nutrients, particularly phosphorus, into the seas. These elements stimulate a rapid growth of plankton – microscopic organisms that absorb carbon dioxide during photosynthesis. After the plankton die, they settle to the bottom, carrying away the bound carbon and thus removing it from the atmosphere for an extended period.

In a warm climate, this mechanism can switch to a different mode. Mass reproduction of plankton leads to a decrease in oxygen levels in the ocean. With a lack of oxygen, phosphorus is less effectively buried in sediments and more frequently returns to the water. This, in turn, fuels new plankton growth, enhances the decomposition of organic matter, and further reduces oxygen levels. Thus, a self-sustaining cycle is initiated, whereby more carbon is extracted from the atmosphere, and global temperatures begin to drop.

Instead of a smooth stabilization of the climate, such feedback can trigger excessive cooling, exceeding the original balance. Computer models have shown that this effect can be powerful enough to initiate an ice age. One of the study's authors compared this process to an air conditioner operating at its limits and 'overcooling' a room. Scientists also note that in ancient times, low oxygen levels in the atmosphere made the climate system less stable, which partially explains the severity of early ice ages. Nowadays, oxygen levels are significantly higher.

Leave a comment