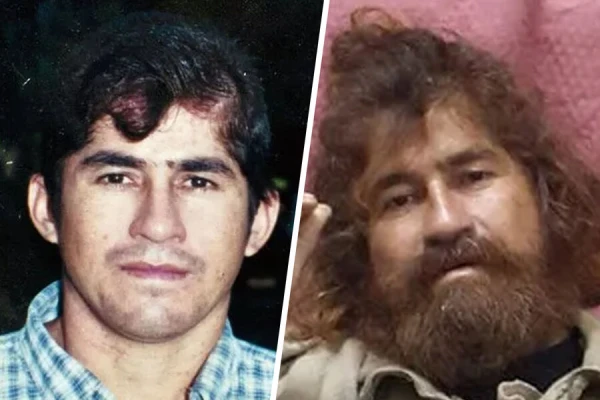

It's hard to imagine that someone could survive so many months at sea.

More than a year on a boat in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. Without supplies, without water, without communication with the outside world, alongside a gradually deranging partner. He drifted side by side with death for 438 days — and, against all odds, survived. This is the story of Salvadoran fisherman José Salvador Alvarenga. When it became known, some simply did not believe him, others accused him of cannibalism.

"The Next Destination is Paradise"

"When he was little, his grandfather taught him to track time by the lunar cycles. Now, alone in the open ocean, he always knew exactly how many months he had been drifting. He knew that 15 lunar cycles had already passed. He was convinced that his next destination was paradise," journalists recounted the memories of fisherman José Alvarenga, who went missing in the Pacific Ocean.

Little is known about his life before this: a simple guy, born in El Salvador, without higher education. He moved to a coastal Mexican village, making a living by fishing, including catching sharks far from shore.

"He found his way of life: a lot of rest, a lot of work, fishing in deep waters," described Alvarenga by the American television channel CNN.

When he was about 37 years old, José, as usual, set out to sea on his 25-foot boat (approximately eight meters long). Sitting next to him was 22-year-old Ezequiel Córdoba — an inexperienced fisherman, but a star of the village football team. He was not supposed to sail with Alvarenga, but, by a stroke of fate, José's regular partner could not make it. Previously, Córdoba and Alvarenga had not communicated, but Ezequiel agreed to substitute for his friend for $50 — money that would cost him his life.

At first, everything went well; in two days, the men managed to catch enough fish that the money from its sale would last a week. Their plans were disrupted by an unexpected storm. The fishermen desperately fought the waves and had already seen the shore in the distance when the boat's engine died. There was no anchor on board (they thought it wouldn't be needed), and the GPS navigator turned out to be faulty (it was not waterproof). Alvarenga managed to contact his boss on the radio.

"Pick us up, things are really bad here!" — the last thing he managed to say before losing communication (to put it in a more censored version).

Trying to lighten the boat, the fishermen threw everything overboard, including all the fish, gasoline, ice from the catch refrigerator, non-working radio, and GPS navigator (the latter, Alvarenga later admitted, he threw overboard in anger). The refrigerator itself became a shelter — the men, curled up and hugging each other, hid from the piercing rain during the storm and from the heat the rest of the time.

The storm lasted several days. When it subsided, the boat was far out in open water. Exhausting, endless months of drifting in the Pacific Ocean began.

Thanks to his skills, Alvarenga was able to catch fish. Occasionally, they managed to catch unsuspecting birds, turtles, and even jellyfish. The latter "burned the throat," but "not so much," as the Salvadoran recalled.

"I was so hungry that I ate my own nails, swallowing all the small pieces," he noted.

To cope with thirst, they drank bird blood and their own urine. The latter would not have saved them — like seawater, salty liquid only exacerbates dehydration. But the fishermen were lucky; they also caught rain and collected water that way.

Unexpectedly, drifting garbage helped. Sometimes, in plastic containers, there were remnants of food. The ocean was so polluted that the same plastic was found in the stomachs of the birds they caught.

Despite having some food and water, Córdoba died after four months.

"Buenos dias. What is it like to die?"

After Alvarenga's rescue, Córdoba's family accused him of cannibalism. What happened on the boat for 438 days is known only from the first's words. One thing is known for sure — two went into the ocean, one returned home.

Alvarenga rejected the horrific accusations, and his lawyer stated that the deceased's relatives were trying to profit from the survivor's fame (the family filed a $1 million lawsuit against the fisherman). In the end, José successfully passed a lie detector test and refuted the suspicions. He himself emphasized that, remaining in the open ocean, he and Ezequiel agreed "not to do that," no matter what happened.

At first, with a supply of food, the two men spent their days on the boat talking. They promised each other that in case one died, the other, if he survived, would find his mother and convey his last words.

"We talked about our mothers. And how badly we behaved. We asked God to forgive us for being such bad sons. We imagined how we could hug our mothers, kiss them. We promised God that we would work harder so they would not have to work anymore. But it was too late," Alvarenga recounted.

Gradually, Córdoba "began to experience physical and mental decline." He could not tolerate raw fish meat, began to refuse food and water.

"He cried a lot, talked about his mom, asked for tortillas and something cold. I hugged him and said, 'We will be saved soon. We will soon reach the island.' But sometimes he would start to rage, shouting that we would die," Alvarenga described.

He tried to feed and hydrate his companion, shoving a bottle of drink into his hand, but he "lost the motivation to bring it to his mouth." Panicking, José begged his companion not to die because he did not want to be left alone.

"On the day of Córdoba's death, it rained... He died with his eyes open. I cried for several hours," the Salvadoran recalled.

After his companion's death, José began to think about suicide, but was afraid he would go to hell. To cope with the despair, he started talking to the corpse, asking it questions and answering himself aloud.

"Buenos dias," Alvarenga said to his friend, who was leaning against the bow of the boat. "What is it like to die?" Ezequiel, whose body had stiffened and turned blue, did not answer. Then Alvarenga answered for his deceased companion: "Good. It’s calm here." He looked at the horizon and the endless ocean. "Why hasn’t death come for both of us? Why do I continue to suffer?" — Alvarenga asked the corpse," CNN described the events on the boat.

According to Alvarenga, he spoke to the dead man for about a week, after which he became afraid he was going insane and threw the body overboard.

"At first, I washed his feet. His clothes were useful, so I took off his shorts and sweatshirt. I put it on — red, with little skulls and crossed bones — and threw him into the water. And when I lowered him into the water, I lost consciousness."

"I Laughed Because I Was Rescued"

During his drifting, Alvarenga saw ships on the horizon — large container ships sailing away. Each time they encouraged him and gave him hope, but the fisherman in his tiny boat had nothing to attract the sailors' attention. He waved his arms and shouted into the void in vain.

To avoid despair, the fisherman immersed himself in dreams. He remembered his family, friends, imagined them nearby. He prayed loudly and sang psalms.

"I walked back and forth on the boat and imagined that I was wandering the world. That way, I could make myself believe that I was really doing something. And not just sitting and thinking about death."

In the end, Alvarenga was saved not by another ship, as he had hoped, but by an island. One day, in January 2014, the Salvadoran unexpectedly noticed that coastal birds appeared in the air. Then a green Pacific atoll emerged from the fog. At first, the fisherman thought it was a hallucination, but then he began to paddle with all his might, and finally fell into the water and swam to the beach.

"I fell on the sand and held a handful of it as if it were treasure... I felt immense relief. I realized that I didn’t have to eat fish anymore if I didn’t want to," he recalled.

The land turned out to be the Marshall Islands — a sovereign island nation in Oceania. Alvarenga was washed ashore on a small island of the Ebon Atoll — one of the most remote places on Earth.

"It’s hard to imagine that someone could survive so many months at sea. On the other hand, it’s just as hard to imagine that someone could suddenly end up on the shore of Ebon," noted later the U.S. ambassador to the Marshall Islands, Tom Armbruster.

There, José was lucky again. He immediately encountered people. The locals looked at the emaciated, unkempt, and wild man with surprise, who was trying to explain something to them in an incomprehensible language and sketch the storm.

"Although we didn’t understand each other, I kept talking and talking. The more I spoke, the louder we all laughed. I’m not sure why they laughed. I laughed because I was rescued," the Salvadoran recounted.

Alvarenga was handed over to the authorities and medical personnel, local media wrote about him, after which he briefly became famous worldwide. Journalists from different countries rushed to the islands to find the incredible survivor. The only telephone line on Ebon became overloaded with reporters trying to find out the details. In a couple of days, José transformed from a fisherman doomed to months of complete solitude into someone dozens of people wanted to talk to. Overwhelmed by such attention, Alvarenga initially avoided the press and was shy to communicate.

"His ankles were swollen, wrists thin; he could barely walk. He avoided eye contact and often hid his face... Dressed in a baggy sweatshirt that concealed his thinness... He quickly smiled and waved at the cameras... He left a note on the doors of his hospital asking the press not to disturb him... He requested to be protected from reporters sneaking into the hospital. He began to call them 'las cucarachas,' or 'cockroaches,'" journalists wrote.

At that time, suspicions began to arise in the media and online that surviving so many months in the ocean without preparation was simply impossible. However, Alvarenga's story was confirmed by both his acquaintances and the authorities, as well as various experts who deemed it plausible. In particular, the local rescue service indicated that it indeed received a report in November 2012 about a missing boat with two such men. The statement was filed by the boat's owner, with whom José managed to speak on the radio.

They were searched from the air for two days and the search was halted due to bad weather. As rescuers clarified, no one was interested in searching for Alvarenga — but the father of the deceased Córdoba constantly waited on the runway.

Alvarenga's family from El Salvador explained to journalists that they lost contact with their son earlier when he went to Mexico. Besides his parents, José's relatives included his 14-year-old daughter. She stated that she hardly remembered her father and could not even imagine his face until newspapers published his photographs on the other side of the Pacific Ocean. After the miraculous rescue, José himself decided to return home.

"We are looking forward to it. We will prepare him a hearty meal, but we won’t feed him fish because he’s probably tired of it," his mother Maria Julio told reporters.

Since then, Alvarenga has lived in El Salvador. He kept his word and found Córdoba's mother, conveying her son’s last words. He quit drinking and published a book about his voyage, which became quite well-known. He has never gone back out to sea again.

"I’m just glad that I’m alive... I suffered from hunger, thirst, and extreme loneliness, but I didn’t commit suicide. Life is given only once — so appreciate it," the fisherman said.