From time to time, conversations about the excessively high salaries of certain leaders of enterprises and institutions emerge in the public space. Many wonder: why, for example, does the rector of a university or the chairman of the board of a state company receive, from the perspective of an ordinary person, an astronomical salary? Moreover, we are not talking about people working in a highly competitive environment, like, for example, "airBaltic," but rather, say (for example), "Augstsprieguma tīkls," which is in a monopoly position, writes Bens Latkovskis on nra.lv.

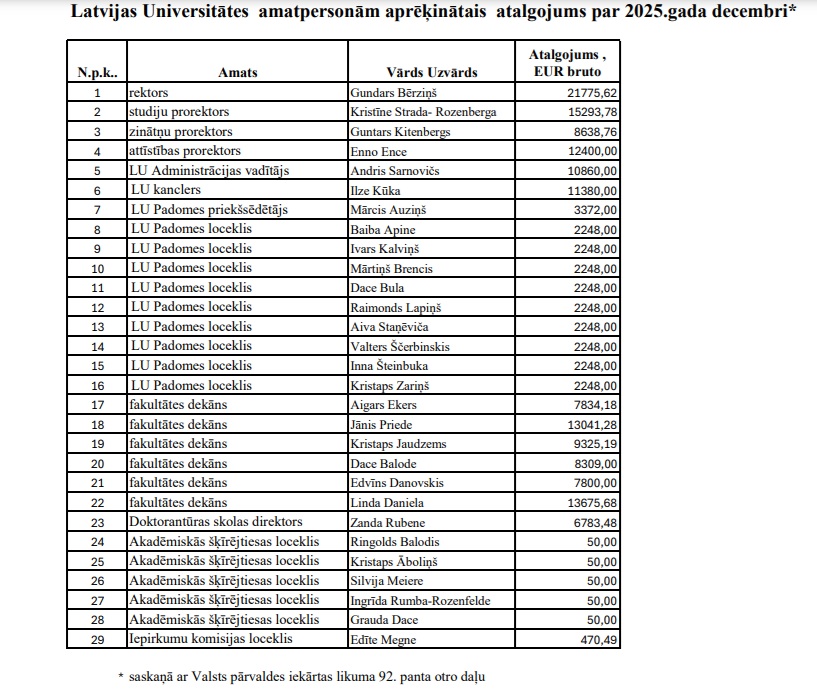

Recently, reports about the "abnormally" high salaries of the management of Latvian universities have resurfaced. The word "abnormally" is in quotes because this concept is relative. For one, it is normal — for another, it is already excessive. In December, the rector of the University of Latvia (UL) Gundars Berziņš received a salary of €21,775.62 (gross); the vice-rector for academic affairs Kristīne Strade-Rozenberga — €15,293.78; the vice-rector for development Enno Ence — €12,400, and the dean of the Faculty of Economics and Social Sciences Jānis Priede — €13,041.28.

Let’s be objective, writes Bens Latkovskis on nra.lv. Maintaining the leadership of the largest and most prestigious university in Latvia on a relatively low salary would not only be inappropriate but also wrong. It would send a false signal to society — as if education and science are not a priority. On the other hand, it would be nice to see some positive dynamics in this very priority.

What is the place of Latvian higher education in the world and how has it changed in recent years? Neither UL nor any other university in Latvia has managed to break into the top thousand of the Times Higher Education (THE) ranking. We are not talking about the first hundred or even two hundred. We are talking about the first thousand. There is not a single Latvian university in it.

But how can we reconcile this with the regular tales that emerge every New Year from the mouths of the country’s top officials about the outstanding achievements of Latvians, including in science? What "outstanding achievements" can be discussed if we are not even in the top thousand, despite considering ourselves part of the developed West? We look at many other countries, not part of the West, with poorly concealed arrogance.

Nevertheless, it is precisely in these countries — Malaysia, India, Saudi Arabia, and others — that there are dozens of universities in the top thousand. Not to mention the many universities in China and South Korea that are not in the thousand but in the top hundred.

Of course, one cannot directly compare the population of Latvia with those named Asian countries, Latkovskis clarifies. They have far more opportunities for selecting and concentrating local scholars, as well as attracting foreign ones. But even in Finland, which can still be somewhat compared to Latvia, two higher education institutions are in the top 200: the University of Helsinki ranks 112th, while Aalto University ranks 195th.

So where does our higher education system stand compared to our closest neighbors? Among the Baltic countries, the University of Tartu leads, ranking 301–350 in THE; Tallinn University of Technology is in the range of 601–800, and Tallinn University is ranked 1001–1200 (alongside UL, RTU, and RSU). The Lithuanian University of Health Sciences is in the 601–800 position; Vilnius University is 801–1000, and Kaunas University of Technology is 1001–1200.

It should be noted that there is another recognized international ranking — QS World University Rankings. In it, RTU is in the range of 761–770, while UL is 801–850. In this ranking, the University of Tartu ranks 358th, and Vilnius University ranks 439th. Both of these schools rank significantly higher than their neighbors.

One can regard these rankings with a degree of skepticism, but they fairly accurately reflect the position of our universities in the global system of higher education and science. There are no more precise indicators.

Returning to the issue of salaries, the main question is how well the remuneration of university leaders corresponds to the final results. Salaries are rising, but there is no increase in rankings. The same 1001–1200 positions for the last three years. In the local European ranking according to QS — UL is going down: 266th place in 2024, 267th in 2025, 274th in 2026.

If the University of Tartu occupies a significantly higher position (140th in Europe according to QS), it would be logical to assume that its rector earns a higher salary than the rector of UL. Moreover, the average salary in Estonia is higher. However, it turns out that the rector of the University of Tartu Toomas Asser earns €140,000–150,000 a year (about €12,000 a month). That is — approximately the same as the dean of the Faculty of Economics at UL. Let’s recall: the rector of UL earns over €20,000 a month.

Unfortunately, not everyone who finds themselves in a high position is capable of managing a large team, the author clarifies. Therefore, it is extremely important that the salaries of top executives are linked to specific results. And there is a huge problem with this. If universities still have rankings for evaluation, then in the case of many institutions and state-owned enterprises — the criteria are extremely subjective.

How, for example, to evaluate the management of a hospital? By profit? By treatment statistics (which can be easily manipulated)? By staff turnover? The same applies to the mentioned "Sadales tīkls" and other state companies, where judging solely by commercial indicators would be incorrect.

In the public sector, it often happens that if a person has entered the circle of "leaders," it is very difficult to exit it — unless they openly start to "break the wood." The main thing is to know how to speak correctly, maintain good relationships with those who can influence your career, and not stand out with excessive activity — "upstarts" are not liked.

Also — one should not overly "stick out" with their salary. This is something that should be more often remembered by those leaders who do not stand out with exceptional managerial talent. After all, it is this insatiability in remuneration (quietly supported by political leadership) that drives society to the very disorders and chaos that always begin with the rise to power of so-called populists (in the past — revolutionaries). Regardless of their views and colors, they know how to "break the wood," concludes Latkovskis.

Leave a comment