Perhaps among them is fiction, poetry – lost masterpieces of which we are even unaware.

In 79 AD, the city of Herculaneum disappeared under the searing breath of Vesuvius. A pyroclastic surge buried the city in a matter of minutes beneath a thick layer of ash, mud, and stones – along with its inhabitants, homes, and a library, the existence of which no one among our contemporaries even suspected. Almost 1700 years later, in 1750, workers digging through hardened volcanic soil stumbled upon the remains of an ancient villa. The luxurious house, lavishly adorned with bronze and marble, would later be named the Villa of the Papyri. Its owner, as historians would establish, was Lucius Calpurnius Piso – the father-in-law of Julius Caesar.

But the main discovery was yet to come: among the debris, strange black cylinders began to emerge, brittle and sooty, like unburned firewood. No one immediately understood that they were the surviving scrolls of papyrus, fused into charcoal by the heat that erupted from the depths of the earth.

In 79 AD, Herculaneum disappeared under the searing breath of Vesuvius. A pyroclastic surge buried the city in a matter of minutes beneath a thick layer of ash, mud, and stones – along with its inhabitants, homes, and a library, the existence of which no one among our contemporaries even suspected. Almost 1700 years later, in 1750, workers digging through hardened volcanic soil stumbled upon the remains of an ancient villa. The luxurious house, lavishly adorned with bronze and marble, would later be named the Villa of the Papyri. Its owner, as historians would establish, was Lucius Calpurnius Piso – the father-in-law of Julius Caesar.

But the main discovery was yet to come: among the debris, strange black cylinders began to emerge, brittle and sooty, like unburned firewood. No one immediately understood that they were the surviving scrolls of papyrus, fused into charcoal by the heat that erupted from the depths of the earth.

Attempts to read the charred scrolls in the 18th and 19th centuries resembled surgical operations – unprecedented scientific zeal bordered on barbarism. Initially, enthusiasts tried simply to saw the scrolls lengthwise and peel off layers of papyrus with a blade. But as soon as a strip was unwrapped, it crumbled to dust. After several such incidents, the royal librarian Antonio Piaggio invented a clever machine in the 1750s: the scroll was secured with threads and carefully unwound, millimeter by millimeter.

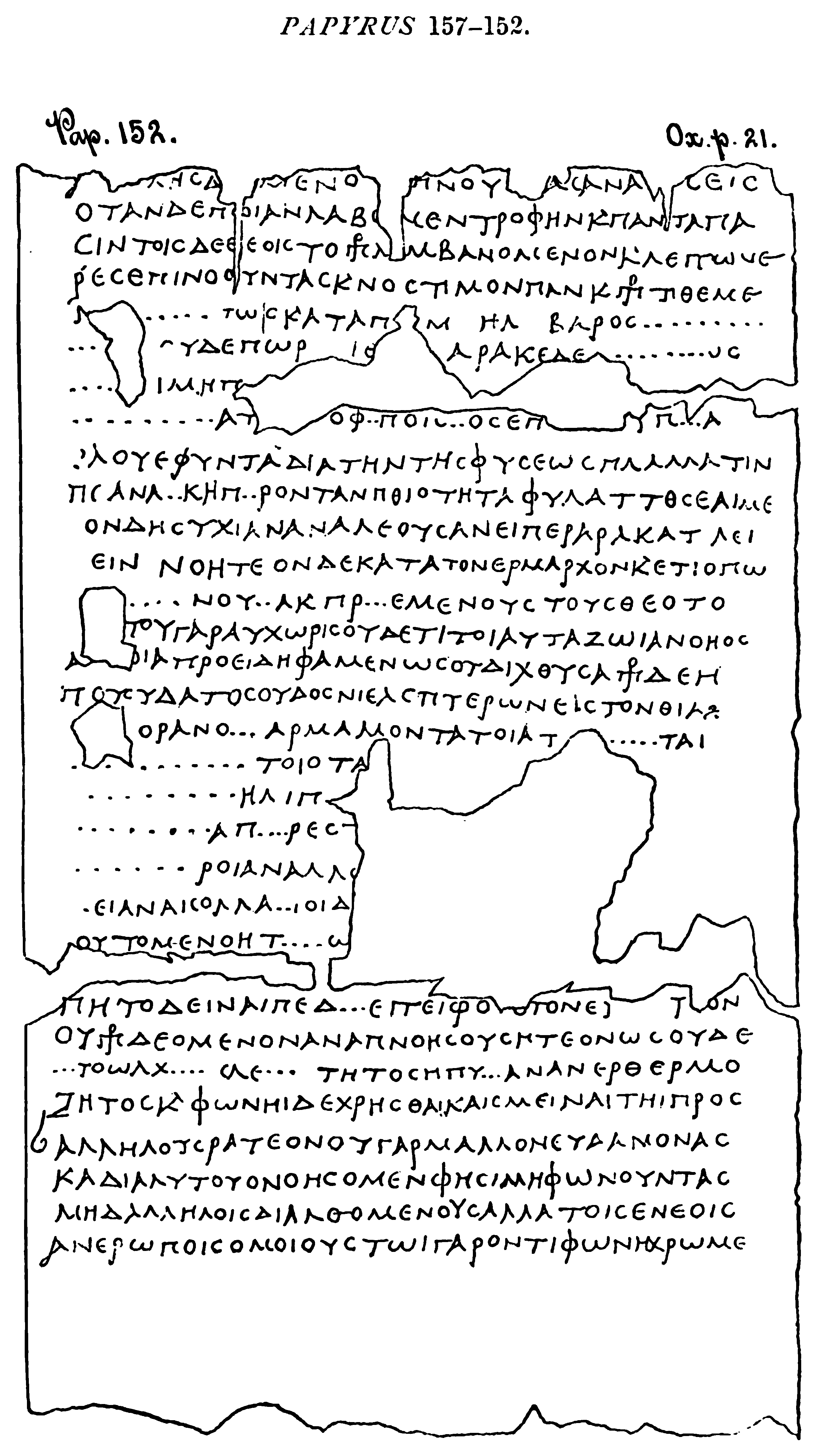

With the help of the machine, Piaggio slowly, with varying success, managed to unroll hundreds of the best-preserved scrolls. This took years: unrolling one scroll sometimes took several years, gluing fragments onto paper. Some texts were read – thus, the world learned of Philodemus's treatises on music, ethics, and rhetoric. But the price was high: many papyri tore, literally disintegrating into dust upon attempts to open them. Experimenters tried everything – soaking the scrolls in chemicals, exposing them to vapors and gases, cutting, crushing.

The mountain of small charred fragments grew. It was such fragments with long-read words that, two hundred years later, would be used as clues for AI algorithms. And hundreds of the most damaged scrolls were decided not to touch at all, so as not to destroy them completely. As a result, about 280–300 scrolls remained securely locked inside their charcoal shells.

The 20th century arrived, but the technologies for reading ancient scrolls had made little progress. Scholars still worked with tweezers and microscopes, publishing barely legible texts by crumbs. The lion's share of Piso's library remained mute. And this silence is especially tragic considering that up to 99% of ancient literature has been irretrievably lost. We know the ancient world only from the meager scraps preserved by scribes in the Middle Ages.

The Herculaneum papyri could have filled this loss, offering us a direct dialogue with antiquity, if only they could be read. But it seemed that there was no chance: the charcoal "books" were too fragile, and the ink on them – black soot – was completely indistinguishable on the similarly charred papyrus. Even when X-ray tomography appeared in the late 20th century and scientists tried to scan the scrolls in their entirety, the problem lay in the invisibility of the ink.

The ink of ancient scribes, as luck would have it, was carbon-based – it contained no metals, which are contrasting for X-rays. On three-dimensional tomograms, the curls of letters remained hidden, indistinguishable in density from the fused papyrus. A miracle of technology was needed to break the two-thousand-year silence.

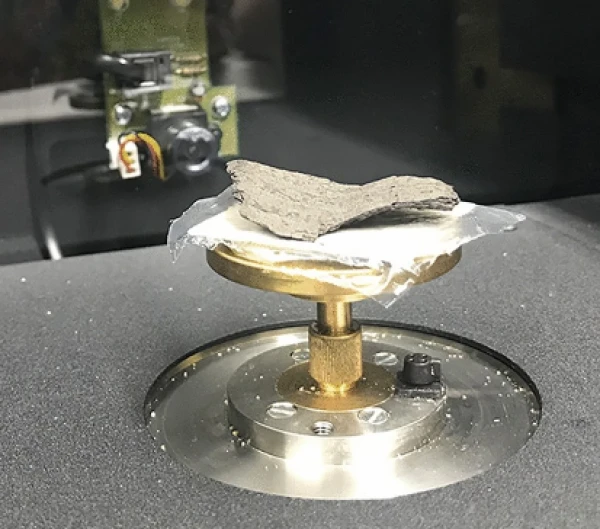

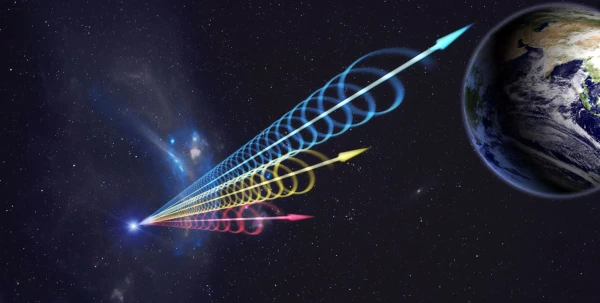

In 2019, in England, at the Diamond Light Source synchrotron accelerator near Oxford, ultra-clear 3D scans of several unopened scrolls were obtained. X-rays penetrated the ancient rolls of papyrus, lying untouched since the time of Vesuvius. A vast array of tomographic data (tens of terabytes) captured the tiniest structural nuances inside the scroll – every surface curvature, every micron of papyrus thickness. But how to recognize letters in this chaos of fine cracks and layers? The task proved insurmountable for the eyes and mind of a single person. It was then that the collective intelligence of scientists and enthusiasts around the world, bolstered by the power of machine learning, came to the rescue.

In the spring of 2023, IT specialist Brent Sills and enthusiastic investors Nat Friedman and Daniel Gross announced the international Vesuvius Challenge with a prize pool of over 1 million dollars. They openly posted the three-dimensional X-ray images of the scrolls and software tools for their virtual unrolling online.

The goal seemed almost fantastic – to train a neural network to read the invisible ink inside the scroll and extract at least four excerpts of text (about 140 characters each) by the end of 2023. Few believed it was possible; the organizers themselves estimated the chances at less than 30%. But the idea infected programmers, students, engineers, linguists, and papyrologists. The project combined competitive spirit with open science: throughout the competition, prizes were awarded for interim achievements, and the code of the winners was made publicly available so that all participants could learn from each other. This significantly accelerated progress.

In the summer of 2023, a turning point came. American physicist and startup founder Casey Handmer, examining the tomograms, noticed a strange texture: a network of fine cracks, like dried mud, covered some areas of the scroll. Handmer hypothesized that this "craquelure" network was nothing more than traces of ink absorbed into the papyrus, slightly altering its structure. Where there were ink strokes of letters, the papyrus cracked in a particular way.

To the naked eye, this invisible text is almost impossible to distinguish, but a computer can detect a barely perceptible signal. 21-year-old student Luke Farritor from Nebraska took advantage of this insight and trained a neural network to recognize the characteristic "craquelure" of letters. At the end of October 2023, his algorithm made a breakthrough: the first word emerged from the scroll – πορφύρας (porphyras), which in Greek means "purple."

For the first time since antiquity, a word from a sealed scroll was read – an event bordering on a miracle. Farritor rightfully received the first prize of the competition for identifying the first letters. And most importantly – he proved to skeptics that the impossible is possible: a machine can read scrolls without unrolling them.

The code was cracked, and all that remained was to continue the work. Within a few weeks, Egyptian Youssef Nader – a graduate student from Berlin – refined the method and was able to visualize fragments of text even more clearly, winning the second prize. The final push occurred in 2024: several teams competed until the last moment, submitting results literally in the final minutes of the deadline.

The "superteam" of three people won – the very Luke Farritor, Youssef Nader, and Swiss robotics student Julian Schilliger. Their collaborative work amazed the jury of papyrologists: the computer revealed 15 columns of Greek text – over 2000 characters, about 5% of the scroll's content. For the first time in 2000 years, humanity was able to peek inside a sealed scroll.

Classical philologist Federica Nicolardi from the University of Naples recalled how experts could hardly believe their eyes when they saw the clear lines of ancient text: "We were completely stunned by the emerging images." For this triumph, the team received the grand prize of $700,000, but more importantly, the very fact of science's victory over time. The ancient manuscript text, buried in Vesuvius, became possible to read. One of the organizers, Kenneth Lapatin from the Getty Museum, called the occurrence the fulfillment of a cherished dream: just recently, it seemed like an "unattainable fantasy" – and now it has become a reality.

What words emerged from the darkness of the scroll? Preliminary translation showed that we received a fragment of a philosophical treatise on the joys of life. The competition organizers jokingly compared it to "a blog post from two thousand years ago on how to enjoy life."

The charred scroll discusses the sources of pleasures – from music to gastronomy. For example, it mentions the taste of capers, the music of the flute, and the purple color of fabrics. One of the curious episodes is the story of a certain Xenophanes, a flutist whose playing was so profound that Alexander the Great himself reached for his weapon. (This is likely an allusion to a well-known story in Plutarch and Seneca – about music igniting the soul of a commander.)

Judging by the style and themes, the author of the scroll is likely Philodemus of Gadara, the very Epicurean philosopher whose library was housed in the Villa of the Papyri. The text has not yet been fully deciphered – the team of papyrologists is now hastily transcribing and compiling it.

However, it is already clear that we are facing a unique monument. This work is not cited in any of the surviving sources, meaning it has not been read since 79 AD.

The themes raised in the deciphered fragments turn out to be surprisingly resonant with modernity. Kenneth Lapatin, curator of the ancient collection at the Getty Museum, notes that Epicurus and his followers pondered questions that concern people even 2000 years later: how to live well, how to avoid pain, what makes life pleasant?

Far from all ancient philosophy has become outdated. On the contrary, some ideas seem to be directed straight at us. After all, essentially, Epicureanism teaches to seek happiness in simple joys, in moderation, in friendship – isn’t that close and understandable to a 21st-century person? And now, thanks to technology, the ancient thinker speaks to us without intermediaries – not in the retelling of a medieval monk, not through quotes from other authors, but in his own voice, recorded on papyrus.

Professor Richard Janko, a papyrologist from the University of Michigan, suggests that this is just the beginning: since this scroll has spoken, there are surely texts of no less value throughout the entire collection. He dreams, for example, that among them are lost works of Aristotle. What if unknown poems of Sappho or Horace, new chapters of Homer, or works of Roman historians are waiting for their moment on the shelves of the Villa of the Papyri? After all, that same library contained Latin scrolls, which, according to reports, contain entirely different content than Greek philosophical treatises.

Perhaps among them is fiction, poetry – lost masterpieces of which we are even unaware. Now that it has been shown that neither time nor the volcano can claim the last word, we are entitled to expect any surprises from the revived scrolls. "These scrolls will reveal unknown secrets to us," enthusiastically predicts Professor Robert Fowler from the University of Bristol.

The victory of artificial intelligence over the ancient ashes of Vesuvius has significance that goes far beyond a single archaeological mystery. Essentially, we have witnessed how memory can await its awakening through the centuries and how modern technology can bring about that awakening. This case is a reminder of the fragility of culture: had the eruption been slightly stronger or a fire occurred during the excavations, Piso's papyri could have disappeared forever.

Moreover, the very possibility of their reading hung by a thread: had it not been for the development of tomography and machine learning, the scrolls would have remained mute masses in storage. The story of the Herculaneum scrolls is the story of the triumph of the human inquisitive mind, which did not resign itself to their silence.

Now that the first text has been deciphered, researchers look to the future with optimism. As early as the beginning of 2025, another scroll was virtually unrolled in Oxford, revealing the Greek word διατροπή ("aversion"), which appeared twice. This scroll, as it turned out, was written with ink of higher density, allowing the letters to appear more vividly in the scans. Even after two millennia, each scroll is unique and presents its surprises: somewhere the ink contains lead and "glows" on X-rays, while elsewhere the text has to be literally scratched out by algorithms from the noise.

The Vesuvius Challenge team announced a new goal: to attempt to read 85–90% of the text from at least a few scrolls. The organizers state plainly: we want to lay the groundwork to later read all ~300 surviving scrolls. And after them, perhaps, the time will come for an even bolder step. Archaeologists have long suspected that there is even more hidden beneath the ruins of Herculaneum: the Villa of the Papyri, as it turned out, had several floors that the excavations did not reach.

Perhaps the main library of the villa lies there – thousands of scrolls containing a wide range of Greek and Latin literature. It is no wonder that scholars say that the discovery of these hypothetical scrolls and their reading would be a sensation comparable to the Second Renaissance. When, during the Renaissance, forgotten works of Cicero, Lucretius, and Vitruvius began to be extracted from the ruins of monasteries, it transformed the culture of Europe. Now we have an equally exciting prospect on the horizon – to lift the veil over a layer of ancient heritage that has lain like a dead weight since the time of the Empire.

However, besides the excitement, this achievement raises philosophical questions. Having received a voice from the ashes, what will we do with it? Will we heed the warnings of antiquity about the transience of life, about the mind and pleasures? Will we realize how easily knowledge can disappear and how unusually it can return? Vesuvius, which destroyed Pompeii, inadvertently sealed a message to future generations in its grave ash. And it took 2000 years and the invention of machine intelligence to read that message.

Our civilization is technological but vulnerable. And the example of Herculaneum teaches us to preserve knowledge. Perhaps we should consider: everything we create today may one day be under a layer of ash (symbolic or literal). Will future generations strive to extract our voices from silence as well?

Leave a comment