Unprecedented mass propaganda was launched.

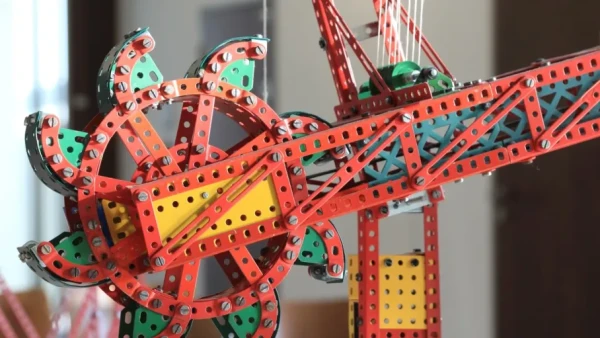

The Meccano constructor — a children's toy invented in the early 20th century by English accountant Frank Hornby — quickly transformed into a successful business and gained worldwide fame. In the USSR, the production of its own Meccano began in the late 1920s: this constructor became the only toy in the country's history around which unprecedented mass propaganda was launched.

At the turn of the 19th century, Frank Hornby, an accountant from Liverpool and a happy father of three children (an English inventor, businessman, and politician. A visionary of the future in the field of toy development and production. — Forbes Life), became fascinated with making mechanical toys. Initially, all his creations were intended solely for his sons. Using narrow metal strips, Frank crafted various trucks, cranes, bridges, and other machinery. "We loved to work and play together, and I always tried to come up with something new for them. In my free time, I mentally returned to our conversations and games, trying to understand how to improve existing designs. It was during one of those moments that the idea for the 'Meccano system' came to me," Hornby wrote in his memoirs. He realized that if standard interchangeable parts were made so that the holes in them strictly matched each other, and the same components were used, it opened up a wonderful opportunity to construct an even greater variety of toys. Thus, in 1901, Hornby filed a patent for the invention "Mechanics Made Easy." The first constructor produced under this name allowed children to create 12 different models from just 16 parts.

The demand for toys began to grow, and by 1905, eight sets had already been released. Two years later, Hornby registered the now-legendary trademark Meccano and founded the toy manufacturing company Meccano Ltd in 1908. Since then, the popularity of Meccano has known no bounds, with sales skyrocketing, including exports. To meet the growing demand, a Meccano factory was built on Binns Road in Liverpool in 1914, which became the company's headquarters for the next sixty years.

Success and high profits allowed for the opening of new branches and the construction of factories outside the United Kingdom—in Germany, Spain, France, and Argentina. In 1916, the monthly publication Meccano Magazine was launched, which later became extremely popular.

The first constructors still had poor durability and roughly made parts — the metal strips and plates were not rounded at the ends, which scratched the hands of young engineers. However, manufacturing methods were constantly improving, and by 1907, the quality and appearance had significantly improved — the strips were now made of denser steel with rounded ends and were nickel-plated, while the wheels and gears were made of brass. In the following years, constructors appeared that could be used to build airplanes and cars. In 1926, to mark the 25th anniversary of his patent, Hornby introduced a novelty — the so-called "colored constructor," whose parts were painted red and green. In 1934, the colors of the parts changed again: the strips became golden, and the plates were blue, with one side cross-decorated with golden stripes. The new color scheme was available only in the United Kingdom and was used until the end of 1945. Meanwhile, the "old" red and green sets continued to be produced for the export market and were reintroduced in the UK after the war. The affordability and accessibility of Meccano sets in the 1930s led to a widespread amateur movement and the creation of societies and clubs throughout Europe, and a special lesson was introduced into the educational program of schools in England and Germany, where children engaged in technical creativity using the now-legendary technical toy.

In the USSR, discussions about English constructors began in the 1920s, but it was not until the end of 1929 that "Meccano-type sets" were put into production. Apparently, the idea of "technical amateurism" appealed to the party leadership of the country, which viewed Meccano as "a serious teaching aid that provides technical knowledge to the worker-inventor" and believed that the new generation should hone their skills in building the new country through the new Soviet toy. The discourse on "Soviet Meccano" acquired not only a political hue but also a state scale. In 1930, one of the central print organs of the Central Committee of the Komsomol and the People's Commissariat for Education, dedicated to the technical creativity of youth, the popular science magazine "Knowledge is Power," launched a permanent section called "Young Constructor," which covered, among other things, "the latest achievements of Meccano in the USSR and abroad." At the same time, the magazine published a note about the creation of the first "Meccano circle" in Moscow.

It is particularly noteworthy that young pioneers held meetings in a private apartment and used a set sent by the brother of one of the circle members from Berlin! Subsequently, the members of the circle planned to transfer their experience to pioneer squads and district technical stations.

An article titled "What is Meccano?" published in the children's magazine "Chizh" (1931) stands out for its enthusiasm: "It can be confidently said that Meccano is the most interesting thing in the world for a little DIY enthusiast."

Here are the arguments in favor of the foreign constructor and "universal technical literacy" presented by the author of the article "What is Meccano and How to Work with It" in an adult publication:

It is much easier and simpler to study the operation and structure of machines on working, moving models. When the Dnieper Construction project was drafted, it was decided to check the accuracy of calculations for its individual structures, particularly the dam. A small model of the Dnieper Construction was built. <...> It was a real little Dnieper Construction that fit on a large table. There was just no water. But then water was released into the model under a certain, pre-calculated pressure. "Dnieper Construction on the table" passed the exam: the model withstood the water pressure in all its parts.

Indeed, Meccano allowed for the creation of a wide variety of models that reproduced real technical structures and the principles of their operation. For example, Alexei Gastev, the founder of the Central Institute of Labor (CIT), developer and ideologist of the Scientific Organization of Labor (NOT), and his colleagues used Meccano to create engineering models, including the mechanism of the social-engineering machine.

The enthusiasm of the authorities and the convincing arguments of leading engineering and technical workers, who saw "huge educational opportunities" in Meccano, ultimately led to the decision to "widely establish the production of Meccano" in the Soviet Union. In February 1929, the Kharkov Metal Stamping Plant named after Medvedev released the first sets of "Soviet Meccano" called "Pioneer" for sale. The cost of a box with an album was 3 rubles and 50 kopecks. "The PIONEER box has been released, American Meccano has been transplanted to our soil," reported the magazine "Knowledge is Power" (No. 4, 1930) in a Leninist manner. That same year, the "Constructor" set was mastered for production "on a mass scale" in Moscow and Leningrad. Depending on the size, number of parts, and configuration, its price ranged from 6 rubles and 95 kopecks to 11 rubles and 30 kopecks.

"Soviet Meccano" is undoubtedly the only toy in the history of the USSR around which unprecedented mass propaganda was launched, reminiscent in its intensity and technologies of today's comprehensive marketing campaigns. Moreover, it not only preceded the release of the constructor but also accompanied it throughout its existence, until the production was discontinued in 1939. "The restructuring of our education to bring it closer to socialist construction will lead to the widespread use of our Soviet Meccano, because it is based on almost literal copying of machines and tools.

Cranes, bridges, cars, machines, mills — these are what the drawings we present in our sample album of what should be built are filled with," writes Comrade M. Kozlov, the manager of the State Plant named after Medvedev, on the pages of the same "Knowledge is Power."

The position of the author of another article, who also discusses the benefits of the English constructor in a complimentary manner, is interesting:

The Komsomol and the pioneer organization, together with the "Tehmass" society and engineering and technical forces, must conduct a public campaign for Meccano. The "Tehmass" society has ordered a complete set of all Meccano sets from England and, upon receiving them, intends to organize familiarization of the broad working masses with Meccano. With the support of the working public, it will undoubtedly be possible to achieve mass production of our Soviet Meccano and its widespread distribution.

It should be noted that at the very beginning of the 1930s, it was still relatively safe to openly express enthusiasm and share enthusiastic responses, even for the appropriated but still "bourgeois" toy. Nevertheless, just in case, to maintain political balance and seemingly fearing their overly "independent free-thinking," the authors timely compensated their laudatory rhetoric by adding the necessary criticism of "alien ideology" to their texts. As a result of such maneuvers, disjointed, quite parodic narratives emerged, such as a fragment from an article by a certain A. Finkel titled "Soviet Meccano" (1930). I will quote it in full: "Models of cranes, tractors, cars, motorcycles, bridges, towers, various machines, excavators, airplanes, and all sorts of devices for illustrating the laws of physics, etc., turn out very well from Meccano. With the help of Meccano, military equipment can also be represented: artillery, searchlights, armored vehicles, machine guns, etc. Thus, the bourgeoisie combines the pleasant with the useful: technical amateurism with the militarization of youth. They manage to use Meccano to conduct... religious propaganda: thus, one of the models depicts St. George the Victorious striking the dragon with a spear."

Equally interesting is an article titled "About Soviet Meccano" in the magazine "Soviet Toy" (No. 6, 1935). The author plays on the existing shortage of parts, trying hard to convey to the reader the idea that "constructions from the sets are only possible with the addition of homemade parts" and ultimately this only "enhances the educational significance of the complex," unlike what happens in the capitalist world, where "the manufacturer tries to give the child everything in ready-made form and reduce play to mechanical assembly."