American scientists have developed a whole scale of storms on our star.

The Sun is continuously "losing weight," scientists have determined. Every second, about 1 million tons of plasma escapes from the upper layers of its atmosphere into space. This unceasing flow has been poetically named solar wind by astronomers.

The plasma in the solar corona is very hot. Its temperature reaches 3 million kelvins, which is approximately 200–500 times greater than that on the surface of the Sun. Scientists do not yet know why this happens. However, it is this high temperature (and therefore high energy) that allows the plasma to influence other objects in the Solar System, determining space weather.

The solar wind is not harmless at all. It likely "blew away" most of Mars' atmosphere in the distant past, turning it into an uninhabitable place. Earth's magnetic field, which the planet acquired early in its existence—more than 4 billion years ago—helps it avoid the sad fate of its neighbor. There are several theories about how this happened, but the dynamo theory is considered the most convincing.

The magnetic field, like a reliable shield, protects us from both the solar wind and solar cosmic rays. Without it, all life on the planet would perish from radiation.

Earth's magnetosphere has to withstand even more serious blows. From time to time, the Sun ejects colossal amounts of plasma in a single burst. The mass of these clumps can reach billions of tons, and they move at speeds two or more times greater than that of the solar wind (hence they are called fast solar wind). Sometimes our planet finds itself in their path.

When a cloud of solar plasma approaches Earth, it deforms the frontal part of the planet's magnetosphere, after which charged particles flow into the tail and stretch it.

At some point, the amount of plasma becomes so great that the magnetic field can no longer hold it. The field lines "break" and reconnect. Part of the plasma flies away from Earth, while the remnants, gaining momentum, return to our planet at high speed.

Particles flow into the polar caps through the outer radiation belt and interact with atoms and molecules in the Earth's atmosphere. This creates one of the most beautiful natural phenomena—auroras. Additionally, heavier particles—protons—enter the inner radiation belt and create ring currents at altitudes of 1,500 to 3,500 km. The resulting deformation of the Earth's magnetic field is called a magnetic storm.

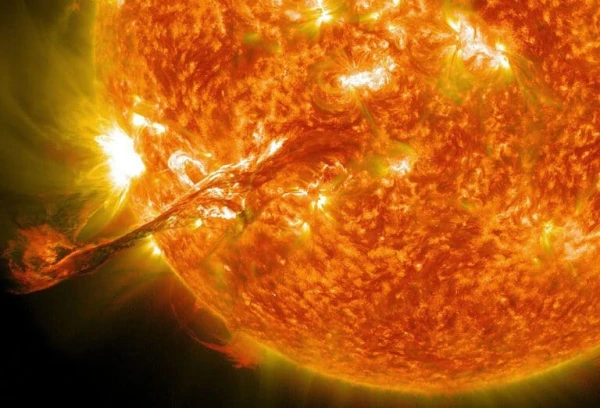

One of the events during which giant clouds of plasma enter interplanetary space is called a coronal mass ejection. Science cannot yet definitively answer why this occurs. Years of observations of our star have helped determine that some ejections are associated with solar flares.

Scientists believe that during such moments, reconnection of loops in the Sun's magnetic field occurs, and the plasma is literally shot into space like a stone from a slingshot. During particularly powerful ejections, the energy accelerates it to several thousand kilometers per second, but usually its speed is several times lower—not more than 800 km/s. The gas cloud reaches Earth in just two to three days.

However, plasma ejections are not always accompanied by flares. For example, prominences can detach from the Sun's surface and drift away without any explosive processes. Their encounter with Earth also disturbs the planet's magnetic field.

Finally, coronal holes—areas of the Sun where the magnetic field is not closed in a loop—can also cause magnetic storms. As a result, plasma ceases to be held at the star's surface and flows away from it in a powerful stream. If we imagine the Sun as the Eye of Sauron, then the dark coronal hole is its pupil. And when Earth comes into its "line of sight," a storm is imminent.

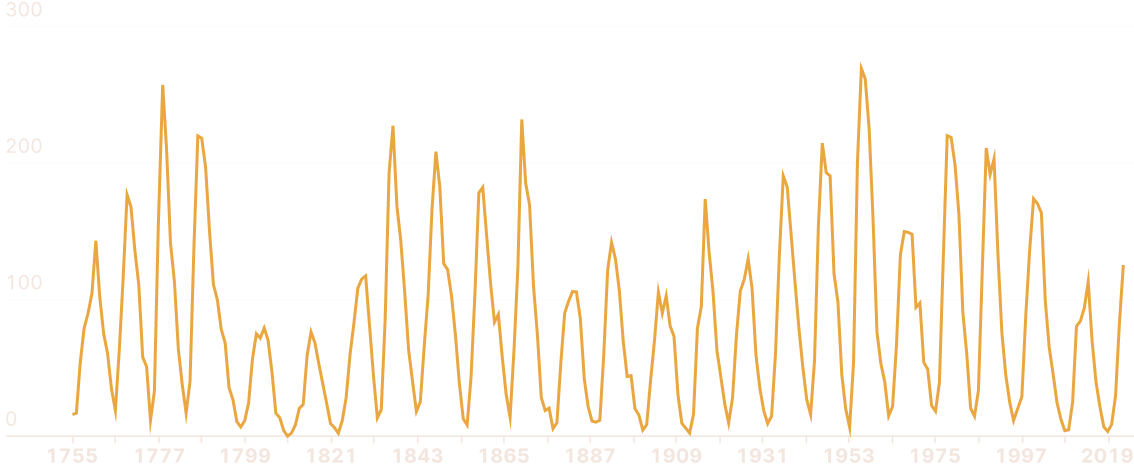

Regular observations of the Sun have been conducted for nearly three centuries—since 1755. During this time, scientists have studied the star well and identified patterns in its behavior—so-called solar cycles. The most famous of these is the 11-year cycle. It is also called the Schwabe cycle, named after the German astronomer who was one of the first to notice the repeatability of certain processes on the Sun.

However, the name "eleven-year" is largely conditional. In fact, the length of the cycle varies from 7.5 to 17 years, but for simplicity, scientists measure time in 11-year segments. The 25th cycle of solar activity began in 2019.

A whole group of spacecraft helps specialists predict magnetic storms. Some measure various parameters of the solar wind (such as speed, density, temperature, etc.) and send information to Earth at intervals of 1 to 5 minutes. Others are directed at the Sun and transmit images of it at different wavelengths. The third group determines the magnetic field strength at the surface of the star.

Scientific equipment is also present on Earth—geomagnetic field disturbances are recorded by special detectors—magnetovariational stations or magnetometers. To assess how much the current situation at the location of the instrument deviates from the norm, scientists use the K-index, and for assessing the global situation, the Kp-index (planetary K-index).

The measurement scale is divided into 10 parts, from 0 to 9. Zero corresponds to geomagnetic calm, and then it increases: Kp=5 indicates a minor magnetic storm, while Kp=9 indicates an extreme one. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in the United States has developed another scale—the G-index. Magnetic storms in this scale range from G1 (weak storm, equivalent to Kp=5) to G5 (extreme storm, Kp=9).