Weighing 144 kg, it could handle an enemy.

In the late 1950s, an unusual three-toed footprint, presumably left by a dinosaur, was discovered in the Petrie quarry in Australia. More than 65 years later, scientists were able not only to confirm this hypothesis but also to identify the imprint as the oldest dinosaur footprint on this continent.

In 1958, a group of schoolchildren led by Bruce Rannegar, who would later become one of the authors of the study, discovered a three-toed footprint on a slate slab in the Petrie quarry in the suburbs of Brisbane. At that time, this site was well known to amateur paleontologists and scientists due to the abundance of Triassic period fossilized plants. Today, the quarry is completely built over.

Despite its significance, the footprint was never formally described in the scientific literature, except for a brief preliminary note. For decades, it was kept in private educational collections, traveling between continents, and only in 2025 was it transferred to the Queensland Museum for comprehensive study. The paleontologists faced the task of investigating a single object, an ichnofossil (fossilized footprint), extracted from its original geological context many years ago. The key goals were to accurately date the footprint and determine the type of animal that left it. The results of this scientific work were published in the journal Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology.

Through geological and stratigraphic analysis, scientists were able to confirm the age of the layers from which the slab originated. The find was made in late Triassic deposits, specifically the Carnian stage, which is about 237-227 million years old. Previously, the oldest evidence of dinosaurs in Australia dated to the later Norian stage (approximately 227-208 million years ago). Thus, the new find "pushed back" the appearance of dinosaurs on the continent by at least 30 million years.

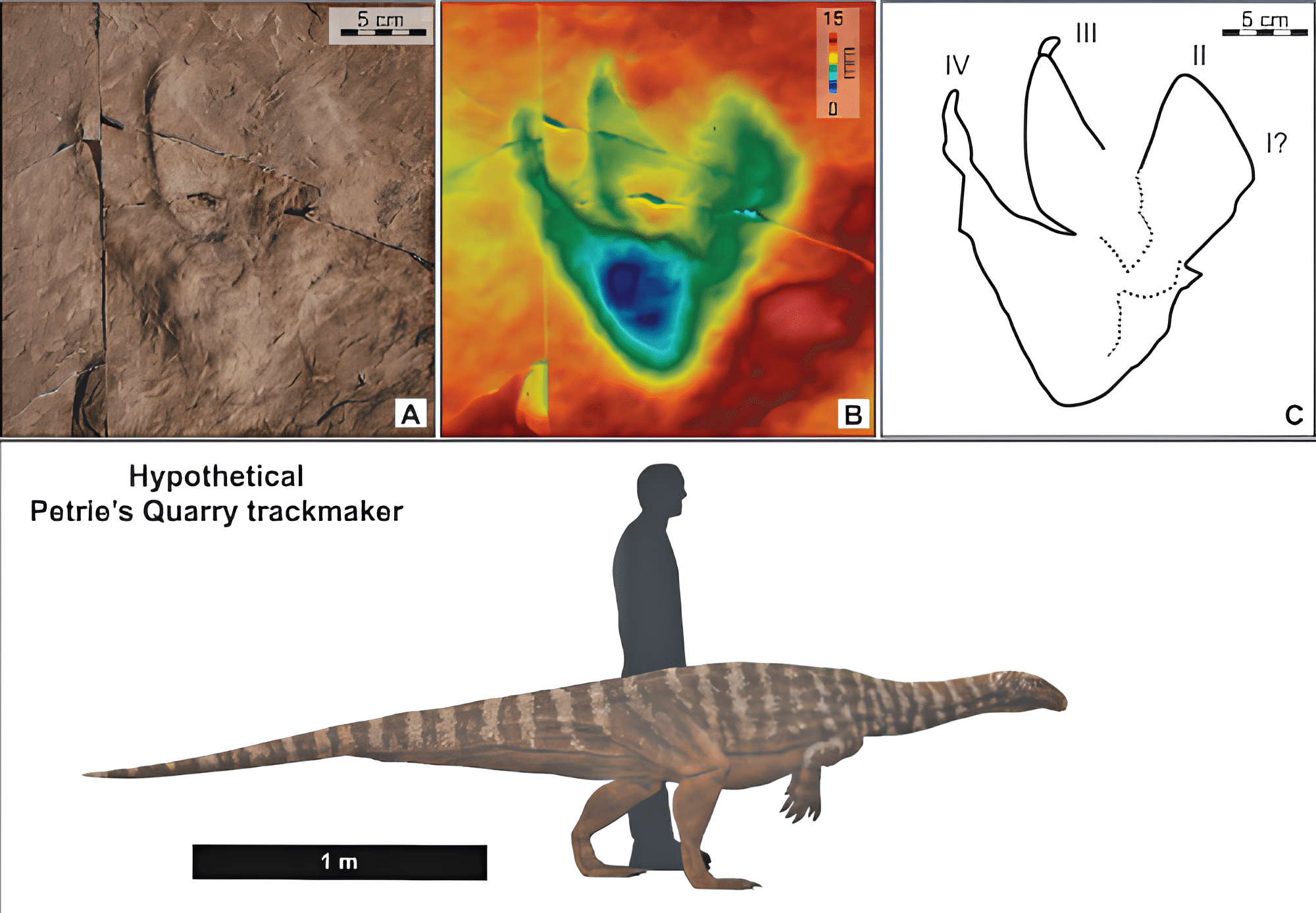

For a detailed study of the morphology of the 18.5-centimeter-long footprint, it was digitized using photogrammetry, allowing for the creation of a high-precision 3D model. To objectively classify the footprint, researchers applied geometric morphometrics, statistically comparing the configuration of key points of this footprint with hundreds of others. Then, using the retro-calculation method and based on the proportions of the skeletons of similar dinosaurs, paleontologists reconstructed the parameters of the animal: its height at the hip was about 78 centimeters, and its body mass was presumably no more than 144 kilograms.

Comparative analysis showed the greatest similarity of the footprint to representatives of the ichnogenus Evazoum. This genus includes footprints that are associated with basal sauropodomorphs—bipedal ancestors of the giant quadrupedal sauropods. The Australian specimen is nearly twice the size of the typical Evazoum sirigui sample found in Italy, indicating a wide range of sizes for these early dinosaurs.

The discovery of Evazoum in Carnian deposits indicates the widespread distribution of this group of dinosaurs across Gondwana—the ancient southern supercontinent—already in the late Triassic. Thus, the footprint found by schoolchildren in the mid-20th century not only set a new record for antiquity in Australian paleontology but also helped scientists better understand the global patterns of evolution and dispersal of dinosaurs.