Washington's diplomacy appears increasingly virtual.

Diplomatic protocol is as significant and deceptive as statistics. Ahead of JD Vance's arrival in Yerevan, there was no clarity regarding his visit to Tsitsernakaberd, the memorial to the victims of the Armenian genocide, which in itself was scandalous.

Laying wreaths at the memorial is a standard and obligatory part of any high-level visit, regardless of the official position of the represented country on the issue of genocide recognition. However, the route and political logic of the U.S. Vice President's trip added an unexpected piquancy to the protocol event.

Vance may not have had elegant options, but what is more interesting in this case is that he apparently did not seek them. He visited Tsitsernakaberd, but upon flying to Baku, he explained himself, and many in Armenia perceived his explanations as justifications: he visited the memorial solely out of respect for the Armenian authorities, who had requested it very much, and the post on X about this visit, which was deleted and then restored, but without mentioning the genocide, was explained by the traditional version already familiar to the White House — a technical error.

In Baku, there were no ambiguities during the wreath-laying at the Alley of Martyrs, victims of "Black January" — the Soviet suppression of the Azerbaijani opposition in 1990 — noted...

The Endless Atom

However, the visit of JD Vance, as it was announced even before it began in Armenia, did not become less historical because of all this. All the bonuses that the Armenian authorities were counting on were received in abundance. The open electoral support for Nikol Pashinyan, which Vance proclaimed several times in different contexts, is among these bonuses, but it is by no means the main one.

Of course, the visit is inscribed in large red letters in the electoral intrigue, with only four months remaining until the resolution. But the secret of the Armenian Polichinelle is that Pashinyan is fighting in these elections not so much against the opposition, which is becoming less convincing, but against the difficulties he creates for himself, and here Vance's help is pleasant but clearly excessive. All this is more of a groundwork for the future that will come after the elections, and today Pashinyan is already decisively preparing for it — perhaps the only one among all Armenian politicians. And if the specifics of Vance's visit evoke memories of Ostap Bender's performance in Vasyuki, then the announced initiatives are quite synchronized with Pashinyan's political program. In this regard, the very idea of TRIPP, the "Trump Route for International Prosperity," looks exceptionally promising. It has no more relation to the real economy than stock market surges, but that’s what the market of expectations is for — to play on it.

The best aspect of this system of announcements has been nuclear energy.

Armenia indeed faces a serious problem — not fatal, but requiring systematic elaboration and political will. The service life of the operating Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant is once again being extended by 10 years, and the option proposed by the Americans for a so-called modular nuclear power plant would be optimal for Armenia. Economically — it is an order of magnitude cheaper than a traditional nuclear power plant. From a safety perspective. From a consumption standpoint — Armenia does not need nuclear giants, and it has nowhere to export electricity. The Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant provides 30–40% of Armenia's electricity needs, and, according to various calculations, two to five modules could replace both the Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant and any other built using traditional technology for significantly less money. The price of the issue is those very $9 billion, which became a sensation of Vance's visit, but the nature of which remains unclear — investments, just the price of supplies, or, as the opposition claims, a new leap in public debt.

But the most serious problem is technological. There is no experience in the industrial use of modular nuclear power plants — neither in the U.S. nor in Europe. So far, projects are either being frozen or becoming more expensive. Thus, the U.S. cannot offer Armenia a real proposal, so the approach is the same as with the "Trump Route" — a cooperation agreement. That is, not even a protocol of intentions.

But before the echo of the proposal faded, Moscow reminded everyone of itself — in the traditional style of Maria Zakharova. On one hand, brotherly, any module, of any capacity, with lenient financial conditions. On the other hand, let the Americans show their product, and in general, Russia cannot calmly watch as an inevitable Fukushima appears next to it.

Strictly speaking, Moscow also has little to show for now, although it may be half a step ahead of the Americans, and possibly even the Chinese. In the Russian Federation, a modular station operates in experimental mode. Russia has a station in Chukotka, but it is floating, which is not entirely relevant for Armenia. Time is not exactly pressing Armenia; according to experts, it has about two years to guarantee completion before the next expiration of the Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant's service life. But if it drags on, time is currently working for Russia — given the current tradition of cooperation, price parameters, and possibly political factors, an urgent solution will most likely be in favor of Russia.

On the other hand, the American proposal, by its very existence, slightly expands the maneuvering room for Yerevan, especially when no one is actually selling anything in this market, meaning there is no need to rush to buy.

Destination — Baku

The same goes for the sale of tens of thousands of NVIDIA chips to Armenia, which optimists saw as an intention to establish their production in Armenia. But it is unlikely that anyone will seriously decide to establish such sensitive technologies in a country that is not in a hurry to rid itself of the risks of Russian expansion, at least economically.

And even less does it look like a revolution what is being declared in terms of security and rearmament — the V-BAT drones promised by Vance to Armenia. No one speaks poorly of them; the question is the amount. The deal for $11 million, considering that not only the device itself is being purchased but also ground equipment, logistics services, etc. — from 3 to 7 sets. In short, both military assistance and such that does not alarm Baku.

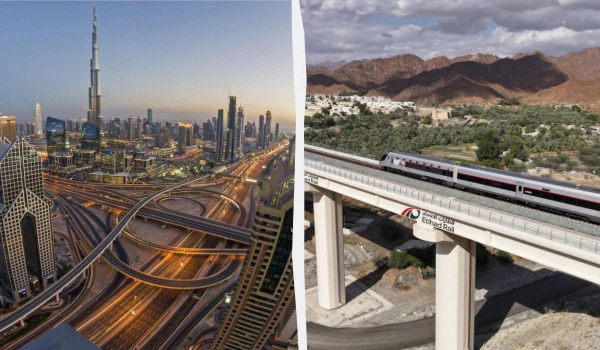

It is precisely Baku, apparently, that is the destination of the "Trump Route," although TRIPP was not mentioned in either Yerevan or Baku, except for a couple of times in subordinate clauses, for example, as a motive for countless private investments in the region. The gifts to Azerbaijan also appear as a set of symbols, and externally not as impressive as in the case of Armenian counterparts. But behind each of these symbols is a designation of quite tangible interest. The boats transferred to Azerbaijan for coast guard duties in the Caspian Sea are, from a military point of view, approximately like drones for Armenia. But the sign is obvious: Baku is not just a military ally of the U.S. but also its representative in a key basin where America is absent, while Russia and Iran are present.

Such a transparent diplomatic style was also demonstrated at the level of what is considered improvisation in the current American administration. The meeting with Pashinyan was so brief that Vance had to explain himself in this case as well: everything that needed to be discussed had already been discussed at the previous meeting, and journalists had to recall its time and place, without much success, however.

In Baku, this informal genre exuded not just a different attitude but also quite practical content: Ilham Aliyev, Vance said, is the only politician, besides Trump, who is friends with both Turkey and Israel. And this is one of the key factors in Trump's attitude towards Aliyev.

The Developer's Secret

Baku, having profitably monetized its neutrality in the Ukrainian war, is undoubtedly close to the current Washington ideas about world order, as is the governing style of Ilham Aliyev. Aliyev can even afford a certain defiance, stating that he will not allow the use of Azerbaijan's airspace for attacks on Iran. But this did not impress Washington: the space in northern Iran is not particularly needed.

Likewise, he will probably regard Armenia's atomic preferences in the same way if it ultimately chooses Moscow. In this sense, the U.S. generally offers to look at itself with optimism to all who have something to offer. Moscow has — control over Armenia's infrastructures: railways, pipelines, and, by the way, political ones. And Moscow is actively offering them, trying to return to the process of grand logistics that Washington announced, from which it was distanced by the efforts of Baku, and then Yerevan, who have tasted the benefits of bilateral resolution without intermediaries. And Washington would probably gladly respond if the basis of its goal-setting were indeed peace as a means of gaining control over this space.

But, as Reagan said, albeit on a different occasion, there are things more important than peace. If those who consider the most accurate metaphor for the current American genre to be the experience of its inspirer in real estate are right, then Vance's journey organically fits into the task of clearing space for a construction site.

What will be built on it is unknown. Perhaps a factory for interplanetary ships, or perhaps a casino. Or maybe nothing, as long as no one else builds anything on it. Or one can simply wait for prices to rise. Everything has been said and heard about investments, military-technical cooperation, strategic partnerships, and general views on logistical corridors and other theses on the ideal arrangement of the world.

And there is no logical foundation that would give all this magnificence an essential connection.

And there is a suspicion that no one is particularly interested in it. Each participant in this act extracts their bonuses, including from the freedom of actions and interpretations, and the complete absence of any binding deadlines.

Armenia, in addition to the European context of its virtually global significance, adds an equally American one. This is not a guarantee of peace, but a legitimization of the infrastructure of reconciliation, the fate of which, however, is still being decided in Baku and Yerevan. Washington's support, if it does not raise Yerevan's stock in conversations with Moscow, diversifies its narrative: with the understanding that the era of monopolies is over, Moscow has already come to terms with it, the window for agreements with Trump is still open, in this multi-move, Armenia can expand its maneuvering space. Not to the extent of revealing to the world the end of history and the beginning of a new one, but compared to the previous tightness, it is quite enough for those who wish to foresee a historical trend.

Azerbaijan receives the same high legitimacy of its new status as one of the leading players in the region, much more than the toponymic convention that was previously known as "the South Caucasus." For Washington, a strong player who can negotiate with both Turkey and Israel and support the conversation about Central Asia in the necessary tone, which, however, no one knows for sure yet, is extremely important. And even its special position on Iran may increase Baku's significance in various combinations, including Russian ones.

And Washington will again fill the global agenda. Placing flags on the territory, camouflaging it with billboards.