Its volcanoes erupt sulfur compounds and silicate lava.

Scientists have asked the question: why are two neighboring moons of Jupiter so different, with Io being volcanically active and Europa being completely covered by a multi-kilometer thick ice crust? One theory suggests that Io was once rich in water, but a recent study deemed this unlikely.

Three of Jupiter's four largest moons share a remarkable common feature — a thick icy crust. In all three cases, the existence of a global layer of unfrozen water is suspected beneath it. It is believed that the heat for this is maintained by the gravity of the gas giant — it subtly deforms the moons as they move along their orbits and creates friction within them.

The same mechanism is considered the source of the spectacular widespread volcanism on Io — the only Galilean moon that does not have an icy surface and shows no signs of water reserves. This world appears completely dry. Its volcanoes erupt only sulfur compounds and silicate lava.

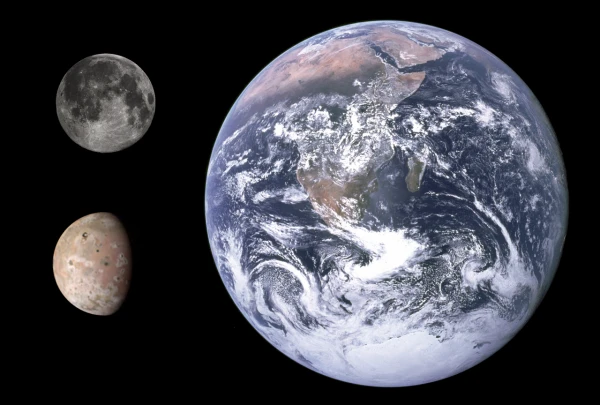

Jupiter's gravity "squeezes" and heats Io the most, as this large moon is closest to the giant — located about 350,000 kilometers from its upper cloud layer. This is less than the distance between Earth and the Moon. The question arose whether this was the reason for the dehydration of the Jovian moon. In other words, was it ever as wet as Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto?

Recently, planetary scientists from the University of Aix-Marseille (France) and the University of Texas at El Paso (USA) attempted to find out. They decided to model the evolution of Io and Europa on the condition that Io also formed as a water-rich celestial body.

In their calculations, they took into account not only the gravitational influence of Jupiter but also that it was hotter and brighter in the early days after its formation. The scientists did not forget about the heat from collisions of small celestial bodies during the moons' growth and the heating from the decay of radioactive elements in their interiors. At the same time, the moons were "placed" in different starting points in the Jupiter system, meaning they considered possible migration scenarios. The researchers explained how the two moons "became" in an article available on the preprint server arXiv.org.

It turned out that initially wet Io and Europa could hardly have reached such different current states under any circumstances: Io would not have completely lost its water even with its intense volcanism. However, as the scientists write, a hypothetical scenario of complete desiccation of the moon could have occurred if it had formed very quickly even closer to Jupiter than it is now.

The problem is that in reality this is unlikely: even in its current orbit, Io is located within the zone around Jupiter where the formation of ice particles and even hydrated minerals — crystals with "built-in" water molecules — is impossible.

The researchers explained that this zone is bounded by the so-called dehydration line of phyllosilicates, and in the Jupiter system, it is located between the orbits of Io and Europa. This means that the largest moon closest to the planet is in a fundamentally different situation even compared to its neighboring moon, let alone the other two. Therefore, the researchers concluded that Io is "built" from dry material.