The head of state has seriously engaged in legislative issues.

As previously reported, today the president decided to send back to the Saeima for revision amendments to the Education Law, which significantly narrowed the possibilities for remote learning for students in grades 1-6 of general education schools. This was already the fourth law that Rinkēvičs has returned to parliament recently due to 'defects'.

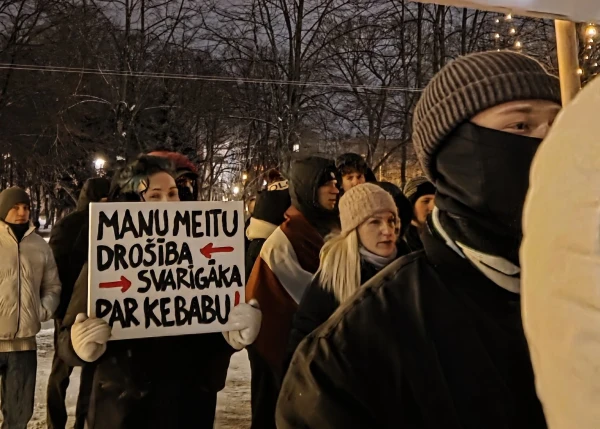

Interestingly, in the previous 2.5 months of his presidency, Rinkēvičs... had not once returned any laws passed by the parliament to the Saeima! The president only stepped on his own song in November of last year when he refused to sign the controversial law on Latvia's withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention. Let us recall: the president not only sent the law back to the Saeima but also suggested... not to consider it in this parliamentary term at all, in other words, to bury it. And most deputies agreed with this!

As they say, a bad beginning makes a good ending, and soon Rinkēvičs sent another law regarding the road toll for trucks weighing between 3 and 3.5 tons back to the Saeima for revision.

In the new year, the president decided to continue this practice and within a week at the end of January returned two laws - first, the head of state refused to proclaim amendments to the law regulating the procedure for compensation for unjustly seized property, and today the head of state dismissed the changes to the Education Law.

Thus, in terms of the number of laws returned to the Saeima, Rinkēvičs has already surpassed his predecessor Levits, who during his entire presidential term, that is, over four years, dared to return only 3 laws to parliament.

What are the reasons for such 'legislative rigidity' of the current head of state?

The first reason is that indeed, as the elections approach, deputies have started to pay more attention to the election campaign rather than the quality of the legislative proposals. Hence the result - the laws being passed have become increasingly one-sided, that is, unbalanced and without consideration of the opinions of those affected by these laws. By returning laws for revision, Rinkēvičs shows parliamentarians that 'this is not how you work' and that the proximity of elections is not a reason to 'cook up' low-quality laws.

The second reason is that looking at which specific legislative proposals the president has returned, it creates the impression that the head of state is also thinking about a second presidential term and therefore tries to maintain political balance even with the returned laws. Judge for yourself. The law on withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention was returned at the request of 'New Unity' and the 'Progressives' party. The second law - on road tolls - was clearly returned in the interests of the opposition and the Union of Greens and Farmers. This was a kind of slap on the nose for the ministers of finance and communications (that is, representatives of 'New Unity' and the 'Progressives' party, respectively).

The return of the law on compensation within the criminal process was made in the interests of 'New Unity' and against the 'Green Farmers', who lobbied for these legislative amendments.

In turn, by returning the amendments on remote learning, Rinkēvičs responded to a request from the United List.

Thus, it can be concluded that all politicians, on the one hand, equally 'took offense' at Rinkēvičs, and on the other hand, it will be more difficult for them to perceive the president as a lobbyist for any one political force - for example, his former party 'New Unity'.

We dare to assume that Rinkēvičs will continue to actively return controversial laws back to parliament.