The history of this find is intertwined with the colonization of India.

In 1972, the "Delhi Purple Sapphire" was found in the storage of the London Natural History Museum — in fact, an amethyst with a mysterious history. The stone belonged to British scholar Edward Heron-Allen and was considered cursed: previous owners faced a series of misfortunes. Heron-Allen hid it in seven boxes and bequeathed that it should not be opened for decades. Today, the stone is kept in the museum.

On a cold morning in early December 1972, Peter Tandy, one of the curators of the London Natural History Museum, went to the warehouse to catalog items that had not yet been added to the lists. He wandered for a long time through the long corridors of this museum labyrinth between huge shelves that reached the ceiling and were filled with strange exhibits that made up part of the vast collection. Eventually, he stopped at a shelf where the oldest exhibits that had not yet been unpacked were stored. Tandy had no idea that he was about to make one of the most astonishing discoveries of his career.

His attention was drawn to a wooden box sitting on one of the shelves. Tandy carefully took it out and placed it on one of the tables. There were no labels or inscriptions on the box. The curator understood that the box could have been sitting on the shelf for decades, waiting for someone to notice it. Well, that day had come. Tandy brushed off a layer of dust from the box and opened it.

To his surprise, inside was another box, and then a third, and then a fourth, and so on, like a matryoshka doll. Finally, on the seventh box, he saw the inscription: "Delhi Purple Sapphire." Intrigued, he opened the little box. Inside was indeed a gemstone; however, it seemed that the inscription was incorrect. What had been stored in this box for years turned out not to be a purple sapphire, but an amethyst. But not just any amethyst. The stone was framed by something like a silver ring with some alchemical and astrological symbols and an engraved Egyptian scarab.

However, the surprises did not end there. Next to it was an envelope. Unable to resist his curiosity, Tandy opened it. Inside was a letter. The paper smelled of antiquity, and the writing style appeared to be manly restrained and elegant, albeit outdated.

Tandy's gaze fell on the date: October 1904. Amazing! It turned out that the gemstone and the envelope had been stored in these boxes for over 70 years. Tandy looked at the signature and was even more surprised. Because the letter was written not by any of his colleagues, but by the famous Victorian writer and scholar Edward Heron-Allen.

But why store this amethyst in seven boxes? Why was it set in a strange silver ring with equally strange inscriptions? What was written in the letter? Without wasting a moment, Tandy read the letter, moving his lips: "To the one who becomes the owner of this amethyst. These lines are a warning for him before he decides to become the master of the stone..."

Thus, after 70 years of oblivion, the "Delhi Purple Sapphire" returned to the world, found in the depths of the London museum.

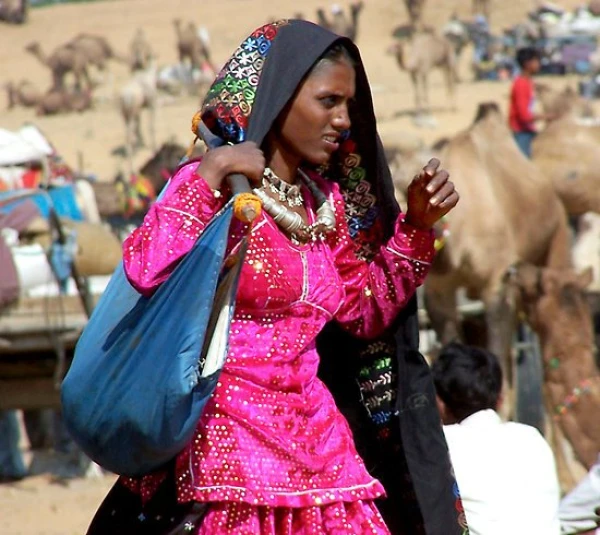

In Heron-Allen's letter, it was reported that the "Purple Sapphire" was originally located in the temple of Indra, the Hindu god of storms and war, in the city of Kanpur, about 475 km from Delhi. In 1857, a rebellion of sepoys, mercenaries of the East India Company, occurred in Bengal. The sepoys had been harboring discontent against the British officers they served for religious, social, political, and economic reasons for years. The British had banned a number of Indian customs such as child marriage, the killing of girls, and the sati ritual (the suicide or killing of a widow on her husband's funeral pyre). Moreover, the sepoys were forced to perform actions that contradicted their caste status, were poorly paid, and faced discrimination.

The last straw was the introduction of the new Enfield rifle model of 1853. The cartridges for the rifle were packed in paper soaked in fat, which had to be bitten to break the packaging. Among the soldiers, a rumor spread that the fat was from pigs or cows, which was blasphemy for both Hindus, who considered cows sacred animals, and for Muslims, who do not consume pork.

The refusal of the sepoys to use the rifle escalated into a rebellion of the troops, which soon engulfed Central India, and then into a full-blown war between Indians and the British, a brutal and bloody confrontation in which both sides committed horrific war crimes even by the standards of 1857.

The 1857 rebellion was so extensive that it led to the dissolution of the powerful East India Company and forced the British to reorganize their army, financial system, and administration of India. Much of the country came under direct rule of the British crown (the "British Raj"), while other regions became princely states subordinated to the British Empire.

Having achieved victory, the British carried out a brutal massacre. Participants and supporters of the rebellion were executed, entire villages were burned, their inhabitants killed, and the survivors were doomed to die of starvation. It was in this situation that Colonel W. Ferris of the Bengal Cavalry seized the "Purple Sapphire" during the looting of the temple of Indra. After the war, he took the gemstone to London, intending to sell it for a high price.

But everything did not go as he expected. No jeweler wanted to buy the stone, and Ferris was unable to sell it. Misfortunes came one after another. The family faced financial disaster, and soon its members, including the colonel, began to fall seriously ill. Then Ferris began to suspect that the cause of all the misfortunes was the sapphire.

When a friend of the colonel, who had borrowed the stone for a time, committed suicide, Ferris's suspicions were strengthened. After the colonel's death, the sapphire was inherited by his son. It seemed that the curse of the stone had intensified: Ferris Jr. lost everything he owned and also fell seriously ill. Desperate, he decided to get rid of the gem. But who could he pass it on to along with the curse? Ferris Jr. thought he should find someone who did not believe in curses and tell him the whole truth about the stone. Perhaps that would make it stop acting. Of course, he was mistaken.

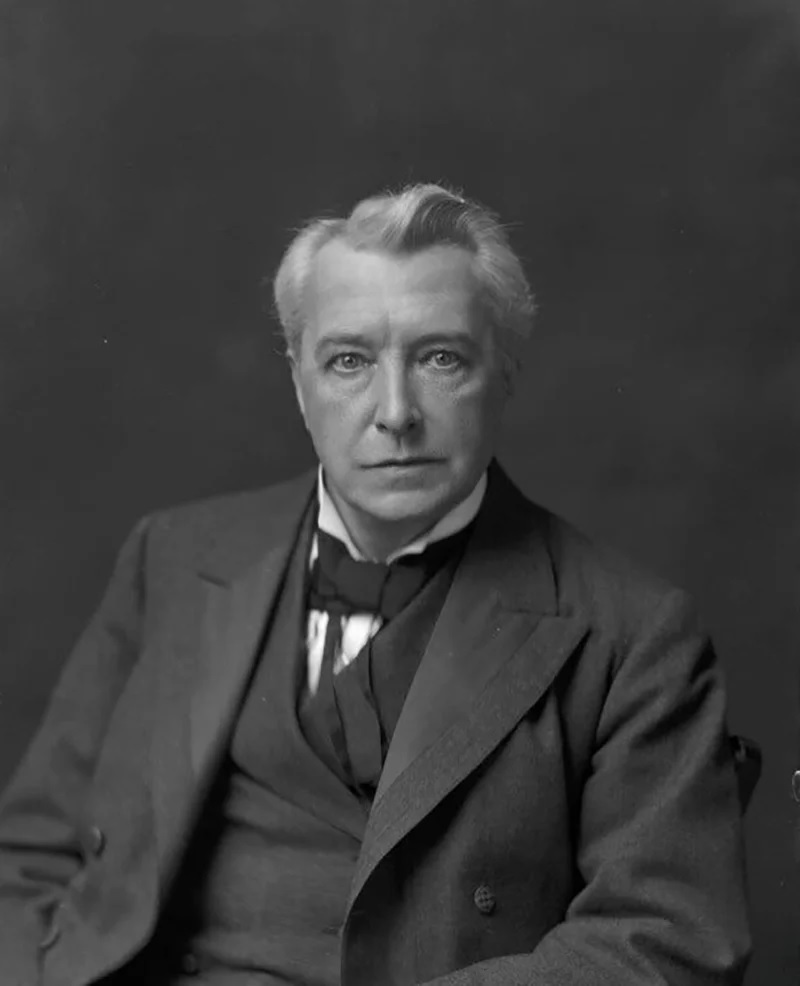

Since he needed to choose someone who would almost certainly not believe in the curse of the gemstone, the most suitable person turned out to be Edward Heron-Allen. Edward was born in London in 1861 and was the youngest of four children of George Allen and Catherine Herring. From childhood, he was interested in classical literature, science, and music, learning to play the violin. He graduated from the prestigious Harrow School, the alma mater of several British prime ministers.

At 18, he began working at the family law firm Allen and Sons, Solicitors in London’s Soho. While working as a lawyer, Edward continued to pursue his interests: he studied paleontology, became an expert in graphology, learned to play the violin and wrote a treatise on the subject, studied the Turkish language, and engaged in translations. Having learned Persian, he translated the "Rubaiyat" of Omar Khayyam and the "Lament" of Baba Tahir, a poem created in a little-known dialect of Luri. He wrote books on history and archaeology, as well as on Buddhist philosophy, natural sciences, and even on growing asparagus. He also wrote many horror and science fiction books under the pseudonym Christopher Blair. He amassed a library of over 12,000 volumes, most of which he donated to the London Natural History Museum. It now bears his name.

As a well-educated man for his time, Edward was not inclined to believe in curses, so in 1890, Ferris confidently passed the equally intrigued yet skeptically inclined scholar and writer the gemstone, sharing its strange story with him.

The new owner was 29 years old and had just married his beloved Marianne. Immersed in his work and studies, Edward soon lost interest in the gemstone and put it away, forgetting about its existence. However, misfortunes soon followed. In a letter found in the box with the stone, he reported that his family had been struck by numerous calamities, and he finally believed that the gemstone was indeed cursed and decided to take measures to neutralize it.

He placed the supposed sapphire in a silver ring belonging to a well-known astrologer named Haydon, adorned with zodiac signs, the Greek letter Tau (which according to Haydon is a sign of protection), and two amethysts in the shape of scarabs from the period of the Egyptian queen Hatshepsut, which were found in one of the temples in Deir el-Bahari opposite ancient Thebes.

The strange protection apparently worked: according to Edward, for a time the curse receded. However, in 1902, a certain ghost-yogi appeared, seen not only by Edward but also by his wife and colleagues. He appeared several times out of nowhere in the library. According to reports, this could have been a mysterious spirit searching for the gemstone: "He crouches in the corner of the room and rummages on the floor with his hands as if looking for it."

The scholar sadly reported that in the same year he gave the gem to a friend, warning him of the danger. Later, the friend returned it, having faced all sorts of misfortunes.

Finally, in 1903, Edward made a radical decision: to get rid of the gemstone forever. He took it out of the house and threw it into the Regents Canal nearby.

The next three months were peaceful in the Heron-Allen household. Confident that he had rid himself of the "Purple Sapphire" forever, Edward was finally able to devote himself again to his pursuits and family. They had a second daughter, and he and his wife were immensely happy.

But fate decided to show him that one cannot so easily rid oneself of a cursed stone. One day, a family friend, a jeweler, came to them with "good news." He pulled a crumpled handkerchief from his pocket, unfolded it: wrapped in the handkerchief was... the "Delhi Purple Sapphire." It turned out that the gemstone had been found by a fisherman and taken to the jeweler to get money for it. The jeweler recognized the stone and returned it to Edward, convinced that he would be pleased with the find.

This time, the scholar was truly frightened. The strange stone had found its way back. How to get rid of it? Pass it on to someone who does not believe in the curse? Edward recounted in a letter that he once gave the stone to a familiar opera singer who had begged for it. When giving the gem, he warned the artist of the danger. During her next performance, she lost her voice forever.

A different way was needed to get rid of the sapphire. Meanwhile, family members began to have health problems, including the newborn daughter. And then Edward Heron-Allen devised a new strategy. He hid the supposed sapphire in the very seven boxes in which it was found by the museum employee, along with a letter outlining the history of the gemstone and warning of the terrible consequences awaiting anyone who wished to possess the sapphire. He then went to the bank and placed the boxes with the gemstone in a safe, stipulating that they could only be retrieved 33 years after his death. Finally, he managed to forget about the gem. Since 1904, nothing had darkened his life. He devoted himself entirely to science and literature. During World War I, he served in the MI7 intelligence unit. In 1919, Edward was appointed a member of the Royal Society of London for his work in foraminifera. He published numerous books — both scientific and fictional.

In 1921, a book of his works was published, which he signed under the pseudonym Christopher Blair: "The Purple Sapphire" and other posthumous works selected from unofficial records of the Cosmopoli University. It tells the story of the cursed sapphire that brings misfortune to anyone who touches it. Was this story inspired by his own experience, or is there something else behind it?

Edward Heron-Allen passed away in 1943 at the age of 81, having received numerous awards for his contributions to science and literature.

However, his wish for the safe to be opened only 33 years after his death seems not to have been fulfilled. Less than a year later, his daughter donated the supposed sapphire to the London Natural History Museum (the gem was registered in the museum in January 1944).

Since then, this amethyst with an astonishing fate has been kept in storage until it was discovered by Tandy in 1972. What happened to the curse all this time? And does it really exist?

The story told by Edward Heron-Allen is so incredible that it is hard to believe in its truth. However, there is certainly a grain of truth in it. The museum's website reports that over the years, several people have contacted its staff to report that the stories outlined in the letter are similar to events that occurred in their families. All of them were from two areas that Edward knew well: Lewis and Sussex.

Moreover, it is quite possible that the writer communicated with one or more officers who participated in the events of 1857 in India and told him the story of the "Purple Sapphire." Undoubtedly, the writer was also familiar with popular novels about cursed jewels that could have influenced his tale, such as "The Moonstone" by Wilkie Collins. Surely he had also read about other cursed gems like the "Hope Diamond" or the "Koh-i-Noor." After all, the story of a gemstone stolen from a Hindu temple does not seem new to us at this stage of reading the book.

Perhaps, to lend credibility to his story, Edward decided to find a real gemstone and pull off the whole scheme with the boxes, the letter, and the bank safe. Of course, the "Purple Sapphire" is extremely rare and difficult to find, so he used an ordinary amethyst. Maybe he just wanted to play a prank on his family. We will never know. It is hard to imagine that an esteemed member of the Royal Society of London would entertain himself in such a way.

In any case, the official position of the museum is that the entire story is fictional and that no curse exists. However, Richard Savin, one of the museum curators, publicly recounted several frightening stories. Savin was tasked with taking the "Purple Sapphire" out of the museum for the first time and bringing it to a symposium organized by the Heron-Allen Society.

At first, everything went smoothly, but upon returning home, he and his wife encountered the most terrifying storm he had ever seen. According to him, one lightning strike hit so close to the car that his wife screamed for him to get rid of the damned gem. He also recounted that every time he had to take the stone out of the museum, he fell seriously ill, but he added that it could have just been a coincidence.

Is the famous amethyst known as the "Purple Sapphire" cursed? Or is it, as museum staff claim, just a story invented by a talented writer? If the latter, for what purpose did he concoct all this? Was it a harmless family prank that spiraled out of control after his death?

We will never know the truth. Edward's grandson, Ivor Jones, showed no interest in reclaiming the gem. Today, the mysterious supposed "Purple Sapphire" is kept in the Natural History Museum in London next to the library that bears the name of its illustrious previous owner, surrounded by other interesting exhibits, probably not as dangerous.

Leave a comment