On his Facebook page, Latvian journalist and writer Imants Liepiņš called for the complete exclusion of Russian classical literature from school programs, stating that its authors historically failed and did not lead Russian society to humanism.

Latvian journalist and writer Imants Liepiņš made a sharp statement, suggesting the complete exclusion of Russian literature from educational programs in Latvia — from schools to universities. In his opinion, even recognized humanists and classics of Russian literature failed to fulfill their main cultural mission. On social media, Liepiņš emphasizes that this is not about rejecting everything Russian as such. The problem, he says, is deeper: “Even truly respected Russian writers — including realists and humanists — ultimately failed in their work.”

Liepiņš notes that many outstanding Russian authors often opposed the authorities, experimented with form, and raised uncomfortable topics. However, despite this, their influence turned out to be minimal: “They failed to guide their compatriots towards a more reasonable path of development.”

“Yes, Tolstoy really tried. But he (and others) failed to make the average Russian reader humane.”

In his assessment, neither the poets of the Silver and Golden Ages, nor the classics of the 19th century, nor the modernists of the early 20th century managed to instill in the mass reader a stable understanding of the value of another’s life and immunity to state propaganda. “Russia, regardless of who is in power, continued to invade, occupy, kill, and destroy,” he writes, pointing out that what is happening today in Ukraine only confirms this trend.

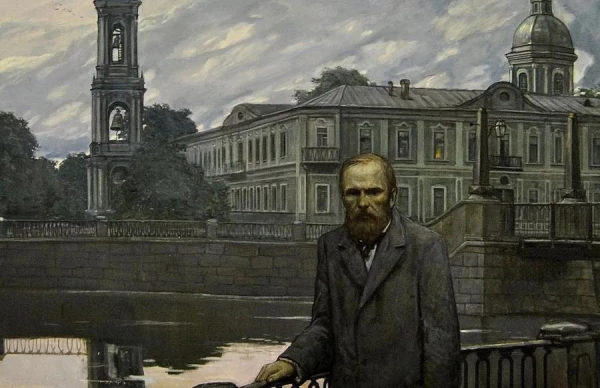

Liepiņš separately discusses imperialism as a systemic feature of Russian literature. According to him, even authors who experienced repression — Pushkin, Dostoevsky, Bulgakov, Shklovsky, Solzhenitsyn — “remained Great Russian imperialists, only in literary form.” Based on this, he concludes: Russian classical literature should not be used in Latvian schools, as “it has not yielded positive results even in Russia itself” and “should be recognized as a failure.”

As an alternative, Liepiņš suggests turning to Ukrainian literature. If it is necessary to study Slavic literature of the 19th century, he advises choosing Taras Shevchenko, Lesya Ukrainka, or Nikolai Gogol, and among contemporary authors — Serhiy Zhadan.

“They, being innovators both in content and literary form, helped to shape a society that today is capable of enduring and achieving the incredible,” he notes.

In conclusion, Liepiņš emphasizes that his position does not deny the efforts of individual Russian writers: “Not because they sincerely did not try to show human values. But because their attempts turned out to be futile.

Leave a comment