To stimulate birth rates, the youth were taxed on contraceptives.

At the end of last year, the Chinese authorities announced the introduction of a 13% tax on contraceptives, including condoms. At the same time, Beijing promised to exempt citizens from taxes on childcare services — nurseries, kindergartens, and other infrastructure intended to ease child-rearing. For decades, China punished its citizens for having 'excess' children, which trapped the country in a low birth rate — where the economy and society are structured around families with one child or none at all — making it extremely difficult to escape, researchers believe. Moreover, neither during the birth control restrictions nor in attempts to stimulate birth does Beijing listen to women's opinions, leading to increased threats against them, including involvement in human trafficking and sexual slavery. In response to state pressure, Chinese women are radicalizing and increasingly prefer not to have children at all.

Demographic Experiment

In the 1970s, China was going through hard times. The country had just begun to overcome the consequences of the 'Cultural Revolution', the economy was depleted, agriculture was inefficient, and the mass famine of the 'Great Leap Forward' was still fresh in memory. Meanwhile, the birth rate remained extremely high: nearly six children per woman. As one of the measures to combat the crisis, the authorities attempted to introduce demographic control.

At the beginning of the decade, Beijing launched a nationwide campaign 'Later, Less, Fewer' (wan, xi, shao), promoting late marriages, limits on the number of children in a family (no more than two in cities and three in rural areas), as well as three to four-year intervals between births.

The state employed a whole range of tools for the first time: free contraceptives, mandatory consultations with specialists, and fines for non-compliance with recommendations. However, these measures did not yield the desired results: by the time the new leadership under Deng Xiaoping took over in 1978, China's population had reached 960 million, while income levels and labor productivity remained extremely low.

In 1978, China's population reached 960 million, while income levels and labor productivity remained extremely low. The new government proclaimed a course towards modernization and rapid economic growth, perceiving the extremely high birth rate as a threat to national prosperity. The architect of China's new demographic policy was an unexpected figure: military engineer, specialist in missile systems and cybernetics, Song Jian.

Borrowing mathematical models from the 1972 report of the Club of Rome 'Limits to Growth', which discusses the collapse of humanity due to overpopulation, Song Jian provided the party leadership with his calculations. They indicated that if the birth rate in China was not sharply and immediately reduced, within the next century the country's population would exceed an apocalyptic four billion people.

Against the backdrop of the weakening of demographic science in China in the 1970s, when many specialists were repressed or driven out of the country, Song Jian's cybernetic approach appeared modern and convincing to the authorities, writes anthropologist Susan Greenhalgh from Harvard. In the absence of alternative scenarios, the idea of viewing the population as a managed system, where birth rate is merely a parameter adjustable at the discretion of the administration, was perceived as a scientifically justified solution.

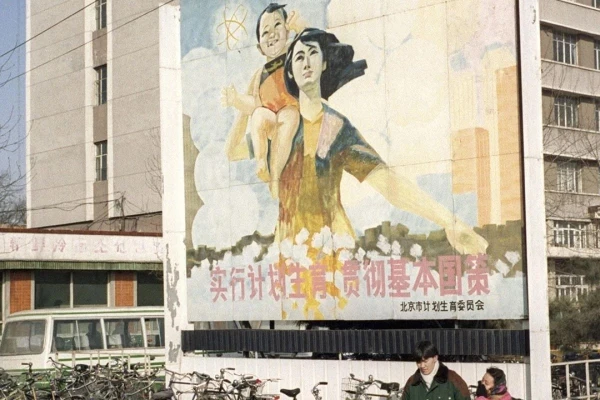

In August 1979, the party introduced quotas for urban families allowing only one child. On September 25, 1980, the authorities published the famous 'Open Letter to All Party and Youth League Members on Controlling the Growth of Our Country's Population' announcing the start of the 'one family, one child' policy — the largest demographic experiment of the 20th century.

Birth control became multi-level. Family planning officers appeared in villages and urban areas, responsible for compiling lists of fertile women, tracking menstrual cycles, recording pregnancies, and mandatory clinic visits. The party's policy was supported by visual propaganda: posters with threatening slogans like 'Better let blood flow like a river than let a child be born out of plan' or 'If one gives birth to an extra child — the whole village will undergo sterilization'.

A 'social tax' was introduced for 'extra' children — a fine equal to the average annual income of the family. Its amount varied by province — from one to three to ten annual incomes. For many, such an amount was unaffordable, leading to the practice of concealing children, especially in rural areas. If a family could not pay the social tax, the birth of a child was not registered in the national household registry (hukou) to avoid punishment. Such children were referred to as 'heihai zi' ('black children') — without registration, they were effectively outside the legal framework: unable to attend school, receive medical services, obtain a passport, or work officially. A fine was imposed for the birth of 'extra' children, equal to the average annual income of the family.

In some rural areas of Guangxi, Guizhou, and Henan provinces in the 1980s and 1990s, the share of 'hidden' children reached 5–15%. Amnesty International recorded cases where parents kept a child at home for years, fearing fines and forced sterilization.

The state distributed condoms and oral contraceptives through medical points in villages and factory medical units in cities. However, the basis of the birth control system consisted of so-called 'passive methods'. After the birth of the first child, women were fitted with an intrauterine device (IUD), and after the second, sterilization was strongly recommended. According to studies, from 1980 to 2014, about 324 million IUD insertions and 108 million sterilizations were performed in China. By the early 1990s, more than 70% of married women were using 'passive methods'.

Birth Rate in a Trap

In the 2000s, demographers began to understand that China's official statistics did not reflect reality. In an article for the journal Population and Development Review, researchers Philip Morgan, Gu Zhigang, and Sarah Hayward recalculated the statistics taking into account unregistered children and found that the total fertility rate (the number of children a woman could give birth to over her reproductive period) in China was below the population replacement threshold — 1.4–1.6 children per woman compared to the normal figure of 2.1.

In 2013, Chinese authorities allowed couples, where at least one spouse was an only child, to have two children. On January 1, 2016, amendments to the legislation allowing any family to have a second child came into effect. In May 2021, Beijing permitted Chinese families to have three children, issuing a document 'On Optimizing Birth Policy and Promoting Long-term and Balanced Population Growth'.

The 'one family, one child' policy contributed to the decline in population growth in China, but it was not the only reason for it. As noted by a group of researchers from the Brookings Institution (Washington, USA), China's demographic indicators are almost identical to those in South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan, where such strict restrictions have never existed.

In all these countries, the total fertility rate has fallen to 1.0–1.3 due to socio-economic changes: accelerated urbanization, rising incomes, mass higher education for women, late marriages, rising housing costs, and high competition in the labor market.

Demographers call this process the 'low fertility trap'. Once the birth rate in society falls below 1.4–1.5, economic models, infrastructure, and social norms begin to restructure around families with one child, and sometimes none at all.

Researcher Shen Shaomin, in her work published in November in the European Journal of Population, points out that the 'one-child generation' is inclined to have even fewer children than their parents. The share of those who prefer not to have children at all has increased two to three times compared to the 1980s generation. If it has become the norm in society to have one child, reversing this trend is nearly impossible.

The share of Chinese people who do not want to have children has increased two to three times in the 2020s compared to the 1980s. According to the Chinese Institute of Demographic Research, the country ranks second in the world in the cost of raising one child until the age of 18. On average, this figure reaches 538,000 yuan ($76,100), while in megacities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen, it approaches 1–1.5 million yuan ($140,000–210,000).

With an average income of young parents at 160,000 yuan per year for both, this means that maintaining one child takes 20–35% of the annual family budget, making a second child financially unfeasible for most urban residents. Therefore, Chinese society did not show much enthusiasm when Beijing allowed families to have more children. Modern couples in the country, if they plan to have children at all, do so at a later age, when they have reached certain career and financial heights.

How Beijing is Trying to Change the Situation

The contraceptive tax introduced in December 2025 is the most high-profile but not the only attempt by Chinese authorities to influence the country's demographics. Over the past five years, dozens of provinces and cities across China have adopted their own programs to increase birth rates, experimenting with direct cash payments, tax breaks, housing subsidies, and extended maternity leave.

The ideological component is also strengthening. In 2021, the State Council of China issued the 'Plan for the Development of Chinese Women' until 2030, which included phrases about 'strengthening national resources' and 'creating a harmonious family'. In this context, state media and party platforms began actively promoting the image of the 'responsible mother', who is expected to 'contribute to the fate of the nation' by giving birth to two or three children.

At the same time, human rights organizations are recording attempts to limit access to abortions, especially for non-medical reasons. Human Rights Watch (HRW) in its report World Report 2025: China points to an increase in gender discrimination and restrictions on reproductive rights. Human rights defenders from Amnesty International note cases where medical institutions were recommended to dissuade women from terminating pregnancies or require additional documentation for these procedures.

A telling example of the Chinese government's encroachment on women's reproductive rights was the case of Xu Zhaozhao regarding the cryopreservation of oocytes. In 2018, an unmarried resident of Beijing approached a clinic to freeze her eggs, but the clinic refused her, citing the Ministry of Health's regulations allowing such procedures only for married women or for medical reasons.

Xu went to court, arguing that the ban violates the principle of gender equality: men in China can freely freeze sperm. In August 2024, a Beijing court rejected the plaintiff's final appeal. Human rights defenders viewed this decision as a symbolic defeat for unmarried women against the backdrop of calls from Chinese authorities to give birth earlier and more.

Women Without a Voice

In trying to stimulate population reproduction, the government completely ignores the female perspective on the problem, which only exacerbates the situation. In the article 'China’s Low Fertility Rate from the Perspective of Gender and Development' (2021), researchers Ji Yuxiang and Zheng Zhou note that domestic labor still falls almost entirely on women amid the necessity to build a career. Motherhood costs Chinese women a slowdown in career growth, a 30–40% drop in income, and additional burdens within the family. These losses cannot be compensated by a payment of 10,000 yuan.

In October 2020, a translation of the article 'We are not flowers, we are a fire' appeared on Chinese social media, outlining the principles of the South Korean radical feminist movement known as 'Six No's and Four T's' (6B4T). This ideology implies a rejection of heterosexual relationships, marriage, childbirth, emotional servicing of men, and adherence to beauty standards. The name is a direct reference to the Confucian code of gender relations 'Three Obediences and Four Virtues', which places women in a dependent position, requiring them to obey their father until marriage, their husband in marriage, and their son in widowhood, as well as to maintain 'moral purity', modesty, and the ability to manage a household.

The Cost of Birth Control

China is aging rapidly. According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China, as of early 2025, the country's population was 1.4 billion people. As research by demographers Xu Jian Pen and Dietrich Fausten indicates, by 2035, a quarter of China's population, or about 350 million people, will be over 60 years old. This means that the 'demographic window', when there were several working-age citizens for each retiree, is effectively closing.

By 2035, a quarter of China's population, or about 350 million people, will be over 60 years old. The aging of the Chinese population creates a serious burden on the pension system, prompting the authorities to undertake painful reforms: starting January 1, 2025, a phased increase in the retirement age began. Over 15 years, it will be raised from 60 to 63 years for men, and from 50–55 to 55–58 years for women, depending on the type of employment. At the same time, more flexible retirement timelines are being introduced, and the period of pension contributions is being increased.

The country is beginning to feel an acute shortage of young workers, especially in low-paid segments of the labor market. If in the 2010s there were over a billion residents aged 15–64 in the country, by 2024–2025, there will be about 880–890 million left. The corporate sector is responding to this problem by expanding automation, while the authorities are discussing attracting labor from neighboring countries. However, China is not yet ready to accept mass immigration that could compensate for the structural shortage of labor.

The 'one family, one child' policy has led to a significant gender imbalance. This was largely related to the traditional patriarchal model of the Chinese family in rural areas: the son stays in the home, inherits the land, and is responsible for supporting parents in old age — because the pension system in rural areas is virtually non-existent.

Birth control restrictions contributed to the spread of this practice: if a family is allowed to have only one child, it must be a boy. As a result, the number of selective abortions using ultrasound diagnostics increased. In some provinces in the 1990s and 2000s, the ratio of newborn boys to girls reached 120 to 100 (with a biological norm of about 105 to 100). According to demographic estimates, by the 2020s, there were over 30 million 'excess' men in China. Entire 'bachelor villages' emerged, where residents over 30 had never married.

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/LDFMSAgKUbA?si=Dhu9mlcFeeyjpXGB" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen></iframe>