According to foreign media, a vast telecommunications and energy infrastructure is laid on the seabed of the Baltic Sea, which is now becoming a serious challenge for security.

As incidents in the Baltic Sea occur more frequently, Poland, Sweden, and other countries are preparing for more effective countermeasures, according to a publication by The Economist, referenced by LA.LV.

The article emphasizes that the control and protection of critical infrastructure in the Baltic Sea is an "urgent national security issue" for Poland and other coastal countries.

On the seabed of the Baltic Sea lie pipelines (Balticconnector connects Finland and Estonia, while Baltic Pipe transports gas from Norway to Poland), hundreds of wind turbines off the coasts of Denmark and Germany, as well as wind farms under construction off the coast of Poland.

There are ten liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals operating on the coast, with two more under construction. Poland is particularly vulnerable, as nearly half of its energy imports depend on pipelines and ports in the Baltic Sea.

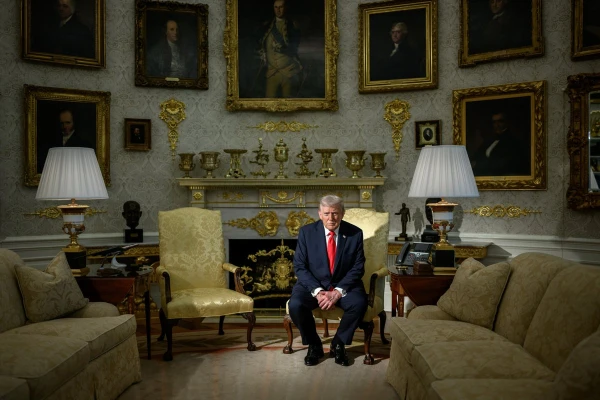

"On paper, NATO's presence in the Baltic Sea has never been stronger. Of the nine coastal states, all except Russia are in the alliance. However, despite NATO's clear superiority in terms of traditional naval forces, Russia still has means to cause damage," the article states.

According to experts, at least 11 suspicious sabotage incidents related to Baltic Sea infrastructure have been recorded since 2023, many of which are attributed to Russia's so-called "shadow fleet."

Among the most serious incidents are the damage to the Balticconnector pipeline and the underwater power cable between Finland and Estonia.

Experts believe that Russia may also use vessels from the "shadow fleet" for operations above sea level. In September, drones, presumably launched from vessels linked to Russia, were spotted over Danish airports. Similar incidents have since been recorded in France and Germany.

"Hybrid attacks allow Russia to deny involvement, test NATO's collective defense effectiveness, and assess each member state's readiness for confrontation. However, Vladimir Putin's regime is acting increasingly openly," the experts add.

In October, Denmark's military intelligence reported that Russian warships had targeted Danish ships and helicopters, simulating a collision.

Challenges in Protecting Infrastructure

The article highlights that protecting underwater infrastructure in the Baltic Sea is an extremely complex task. Although radars and satellites allow monitoring of airspace and ships even with transponders turned off, the seabed is an "ideal environment for hybrid attacks."

Most tracking technologies based on sonar are ineffective in the Baltic Sea. Shallow waters, dense seabeds, and intense shipping create acoustic interference, while sharp changes in salinity distort sound waves.

Hydroacoustic sensors, A26-class submarines, and unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) may offer partial solutions. However, developing an integrated monitoring system—one of NATO's key objectives—will take several years.

Countering Hybrid Attacks

Meanwhile, the UK's Defence Intelligence has concluded that Russia is modernizing its fleet to attack underwater cables and pipelines. Therefore, as The Economist emphasizes, "NATO must do more to show Russia that its hybrid attacks will not go unpunished."

The alliance has already increased patrols in the Baltic Sea; however, international law prohibits inspecting third-party vessels without permission.

Some states are proposing more radical measures. Following the appearance of drones over Denmark, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky suggested closing the Baltic Sea to tankers from the "shadow fleet." A similar initiative was previously put forward by Estonia's Minister of Defence Hanno Pevkur.

However, as The Economist points out, such a blockade would almost certainly violate international law. The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea guarantees vessels, including those under sanctions, the right of passage through international straits, provided they do not pose a security threat.

Russia, which transports about 60% of its maritime oil exports through the Baltic Sea, would likely view the closure of Danish straits as an act of war.

An alternative option could be a ban on the passage of vessels that do not meet technical standards—such practices are gaining popularity. In October, Denmark intensified control over tankers at the port of Skagen, which connects the North and Baltic Seas. Poland, in turn, is strengthening its naval forces— in November, parliament passed a law allowing the use of the fleet to protect critical infrastructure even beyond territorial waters.

As previously reported by UNIAN, the Swedish Navy encounters Russian submarines in the Baltic Sea almost every week. In response to the growing threats, Sweden and eight other countries recently conducted large-scale military exercises.

Leave a comment