Shallow coastal seas became land, and marine life retreated to deeper seas.

All terrestrial vertebrates, including us, evolved from fish, but how exactly fish became the dominant inhabitants of the seas remained unclear until recently. The authors of a new scientific paper attempted to prove that the cause of this was an extinction event possibly triggered by white nights.

Before the Late Ordovician extinction, which occurred in two waves 443-445 million years ago, the world looked fundamentally different from later eras. It was not only that the continents were almost lifeless by modern standards, with rare arthropods crawling ashore from the sea and liverwort-like plants on coastal rocks. The sea was different too: it had virtually no modern-type fish.

It was dominated by jawless fish similar to modern lampreys and hagfish. As the name suggests, they lacked jaws and attached to food with a round mouth. The picture was completed by huge trilobites, shellfish, sea scorpions the size of humans, and enormous nautiloids—actively swimming predators with pointed shells up to five meters long.

Today, there are only a few dozen species of jawless fish among vertebrates, while there are another 70,000 species of jawed fish. These include both bony and cartilaginous fish (sharks and rays), and, secondly, tetrapods—meaning all terrestrial vertebrates, including us. Tetrapods also evolved from fish, so understanding the origins of the latter would be very beneficial. However, this is difficult to achieve: early fish were rarely preserved, as they were often small and made up of poorly preserved soft tissues. Therefore, it is very challenging to determine when exactly they began to displace jawless fish, and if that is the case, it is impossible to understand why this happened.

The authors of the new paper, published in Science Advances, tried to fill this gap through a systematic analysis of all jawed fish findings prior to 400 million years ago. They concluded that the cause of their evolutionary boom was the Late Ordovician extinction, although initially it dealt with them very harshly.

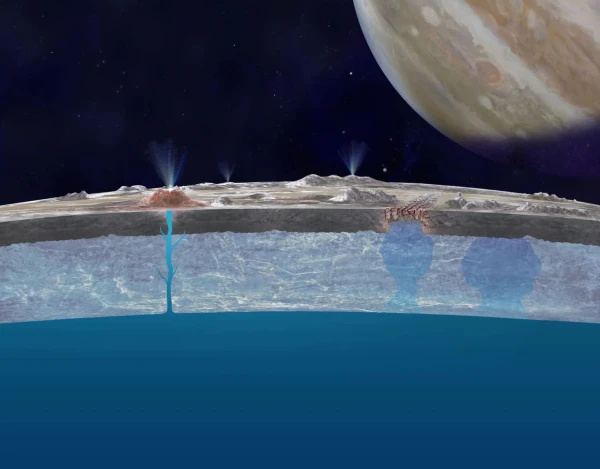

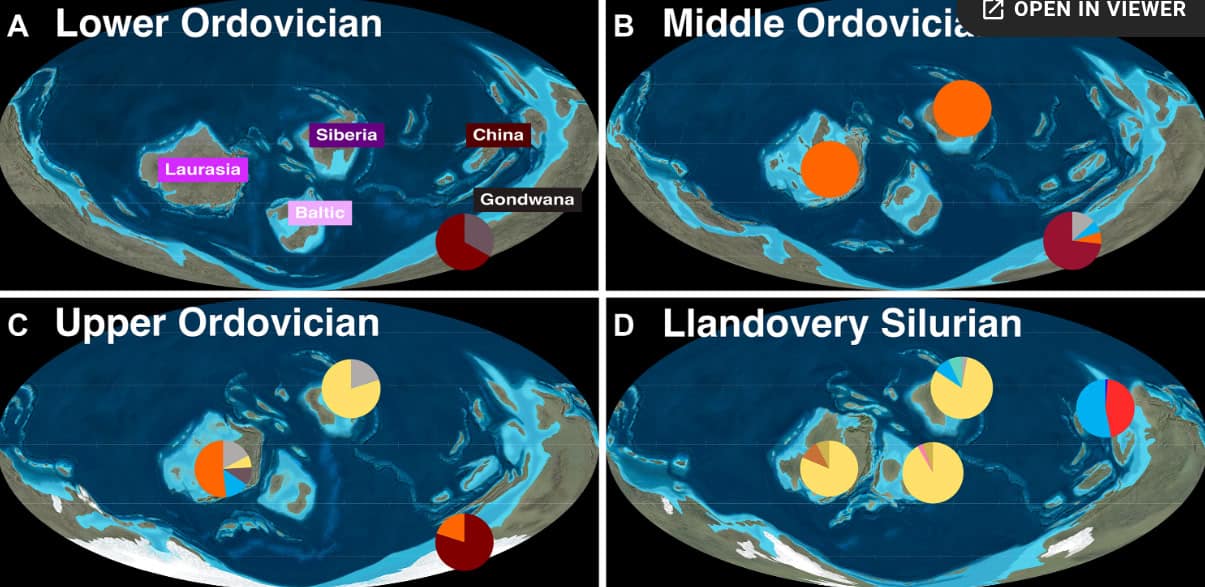

The researchers analyzed the diversity of both jawless and jawed fish during the Late Ordovician extinction. The first wave, 445 million years ago, began with a severe cooling: massive glaciers formed on Gondwana, which lay in the southern hemisphere. As a result, shallow coastal seas became land, and marine life retreated to deeper seas. Biodiversity radically decreased, both among jawless fish, which dominated in terms of species count, and among jawed fish, which were still very few.

The second wave of extinction, also associated with sharp climate fluctuations, occurred about 443 million years ago. It again reduced the diversity of marine species, but after it, over the course of several million years, many different groups of jawed fish, unique early fish including sharks, appeared. Moreover, these species were very different in different regions. This distinguishes the situation from the preceding Ordovician extinction, when jawless and jawed fish were quite similar throughout the global ocean.

The researchers believe that climate fluctuations destroyed the unified global marine ecosystem: new marine ecosystems were often isolated from each other by geographical barriers. Even when the climate became warm again and shallow seas began to connect with the global ocean, the spread of species formed in different regions occurred very slowly. Apparently, the newly emerged fish species swam poorly in the open ocean or could not find food in it to spread over large distances.

Nevertheless, the timeline of the appearance of those groups of jawed fish that we see after the extinction 445-443 million years ago indicates the key role of this event in the sharp increase in fish diversity. They did not immediately completely displace jawless fish, but the trend toward this began around 440 million years ago. Thus, the dominance of fish and their tetrapod descendants in terrestrial ecosystems should be traced back to the Late Ordovician extinction.