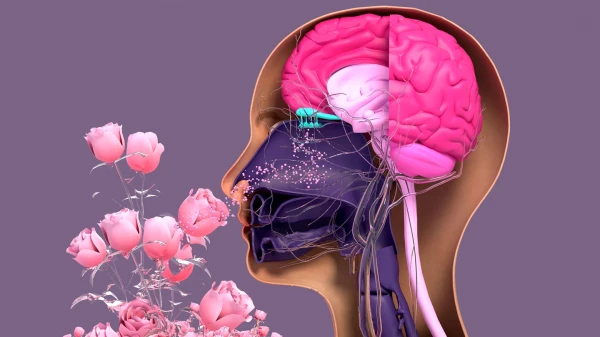

There is an enormous number of different molecules in the air, and odors typically consist of complex combinations of them.

A team led by the RIKEN Center for Brain Science in Japan has discovered how animals distinguish pleasant and unpleasant odors—a capability closely linked to the perception of food taste. The researchers found that these sensations are processed by different neural circuits in the brain and are not simply opposing signals. The results of the study were published in the journal Cell.

Olfaction is one of the oldest senses, having emerged in aquatic vertebrates and based on the function of chemical receptors. In mammals, molecules from the air enter the nose, where they interact with receptors on olfactory neurons that transmit signals to the brain. Since there is an enormous number of different molecules in the air, and odors typically consist of complex combinations of them, evolution did not follow the path of "one odor – one receptor." Instead, each scent is encoded by a multitude of overlapping neural signals distributed across different areas of the brain, significantly complicating the understanding of the mechanisms of odor recognition.

In such cases, scientists often turn to animal models, where the nervous systems are simpler but operate on similar principles. The team chose to study the fruit fly, whose olfactory system can be examined in detail—down to individual neurons and their connections. However, even in a fly, there are thousands of neurons and hundreds of thousands of connections, making the task extremely challenging. To tackle this, the researchers developed a method that allows them to record the activity of all neurons in different regions of the fly's brain by combining two-photon microscopy with optogenetic labeling of cells. Additionally, they constructed a network model that reproduces the functioning of these neurons based on the connectome—a map of all the connections between them. This enabled a deeper understanding of how the neural circuits responsible for processing odors are structured.

The scientists found that neurons in a brain area called the lateral horn are responsible for the innate perception of odors as pleasant or unpleasant. According to the model, unpleasant odors cause direct excitation of these neurons, while pleasant ones are formed through additional local inhibition. An unexpected finding was that the evaluation of pleasant and unpleasant odors occurs in different neural circuits, which are not only physically separated but also have different types of connections. In other words, in the brain, "pleasant" is not simply the opposite of "unpleasant"—it is a separate information processing process.

The researchers applied optogenetics to test the predictions of their model. This method allows for precise activation or inhibition of individual neurons. Thus, when the model predicted that suppressing a certain local circuit would cause the flies to stop perceiving a normally pleasant odor as their favorite, the experiment confirmed this prediction.

Leave a comment