Sensational discoveries have been made in China.

A new analysis of fossils found in China has shown that the history of sapiens, Neanderthals, and Denisovans may have begun much earlier and was likely far more complex than textbooks suggest. An international team of scientists has challenged the conventional timeline of human evolution. However, there are several questions regarding the researchers' conclusions.

For a long time, the picture of Homo evolution resembled a linear genealogical tree. One branch replaced another, gradually leading to the emergence of Homo sapiens. However, discoveries in recent decades, particularly in the field of paleogenetics, have shown that the reality is much more complicated. Several species of humans coexisted on the planet simultaneously, intersecting, competing, and even interbreeding.

The key players in this drama were the Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) — inhabitants of Europe and Asia who disappeared approximately 40,000 years ago — and the Denisovans, who populated vast territories of Eurasia. The latter went extinct, according to various estimates, 30,000 to 50,000 years ago.

For 15 years, Denisovans were known to science only through a couple of isolated teeth, jaws, and fragments of DNA extracted from a pinky bone found in Denisova Cave in Altai. This ghostly, "genetic" reputation made them a major mystery in paleoanthropology.

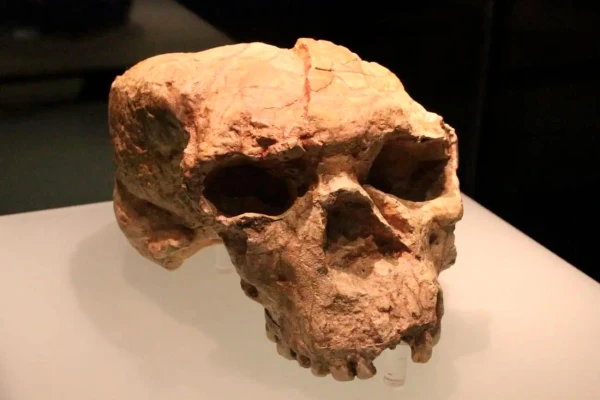

The situation began to change only recently. Scientists finally obtained material evidence of the Denisovan appearance. A crucial step was the description of a massive intact skull of an ancient human found in Harbin in northeastern China. Initially, the find was attributed to a new species, Homo longi, but molecular analysis showed that the fossil belonged to a Denisovan who lived over 146,000 years ago.

Genetic data convincingly proved that modern non-African humans carry a small percentage of Neanderthal genes. As for traces of Denisovan DNA, there is an uneven distribution across continents: Denisovan genes are found in Papuans of New Guinea, Aboriginal Australians, and a small percentage in the populations of East and Southeast Asia, while significant Denisovan heritage has not been found in some African populations, nor in many Europeans. In any case, this data indicates that the ancestors of sapiens encountered and interbred with these two species.

According to the accepted model based on DNA analysis, there existed a certain ancestral population, informally referred to by scientists as "Ancestor X." Approximately 500,000 to 700,000 years ago, this population split. One group gave rise to the line that evolved into Homo sapiens in Africa. Another group migrated to Eurasia and later, between 400,000 and 500,000 years ago, split again, forming the lines of Neanderthals and Denisovans. This scheme had served for decades as the basis for understanding the past of Homo. But the authors of the new study, the results of which are presented in the journal Science, have questioned its accuracy.

During archaeological excavations near the river terrace of the Han River in central China, scientists found two skulls of ancient humans. Both finds had suffered greatly over the hundreds of thousands of years spent in the ground: layers of soil had flattened them. But an international team of anthropologists and paleogeneticists led by Chris Stringer from the Natural History Museum in London decided to revisit the mysterious skulls. The researchers employed advanced technologies, including computer tomography and special algorithms, which allowed them to virtually "clean" the bone from the surrounding rock. They literally pieced together a digital reconstruction of the Yunxian-2 skull, restoring its original shape.

Analysis showed that the skull is between 940,000 and 1.1 million years old. Hominins of this age have traditionally been classified as Homo erectus. This species appeared in Africa approximately two million years ago and widely settled in South Asia, reaching Indonesia, where its representatives lived for hundreds of thousands of years and disappeared approximately 108,000 years ago.

Leave a comment