The cosmopolitanism of ancient art was palpable.

For five years, a team of historians and archaeologists from the University of Leicester tried to unravel the mystery. Beneath the quiet fields of Rutland, far from the sunny ruins of Greece or Turkey, lay one of the most remarkable Roman mosaics ever found in Britain — a vast, masterfully crafted piece, unlike any other on the island.

But its true value was only revealed recently when researchers realized that they were looking at a narrative that the modern world had almost completely forgotten, writes the portal Arkeonews.

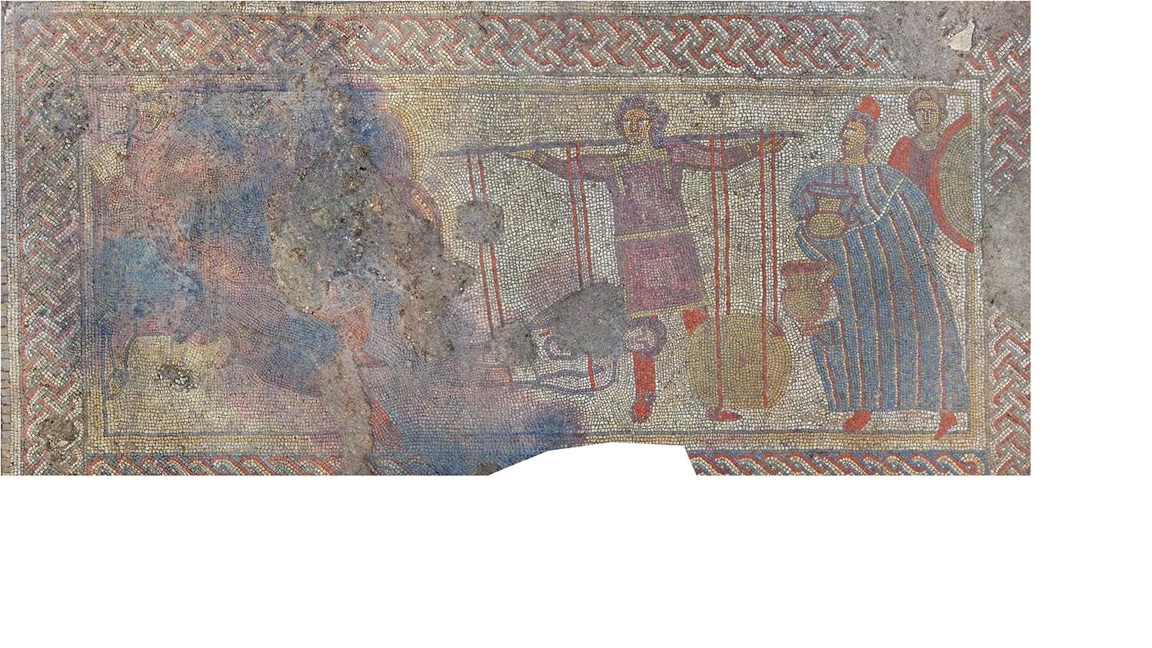

The story of the Ketton mosaic, created around 1,800 years ago, is based on a forgotten work by Aeschylus — the great Athenian tragedian whose plays once captivated ancient audiences. His tragedy "The Phrygians," lost over the centuries and preserved only in a few mentions, unexpectedly emerged as a large-scale visual narrative — in the mosaic on the floor of a villa on the northern edge of the Roman Empire.

It was discovered in 2020 during the lockdown due to the pandemic. Farmer Jim Irwin noticed fragments of stone with a pattern on his property. He reported the find to specialists. Ultimately, the University of Leicester and the organization Historic England got involved.

What the archaeologists uncovered astonished everyone: a large, wealthy Roman villa, and in its central room — a massive mosaic nearly 11 meters long, a true stone canvas depicting scenes of war, grief, and grandeur.

The narrative unfolds in three scenes, each dedicated to the rivalry between Achilles and Hector. The duel itself is conveyed with dynamic force: the figures are caught in a tense moment before the strike. The next scene shows the aftermath — Achilles racing in a chariot, dragging Hector's lifeless body behind him. But it is the final fragment that surprised scholars. There, Hector's body is weighed on scales against gold, for which King Priam redeems his son.

This episode is not found in Homer. It belongs to a lost version of the myth created by Aeschylus — an alternative narrative known only from ancient commentaries and now from this mosaic. This detail shows that the villa's owner and the artisans who created the mosaic floor relied on a version of the Trojan legend that was already rare in the Roman era.

Such connections challenge the long-held notion of Roman Britain as a cultural backwater. On the contrary, they reveal a province integrated into the flows of Mediterranean art, trade, and intellectual life.

The villa's owners were undoubtedly educated, affluent, and ambitious individuals — those who saw value in filling their home space with stories that traced back to the deepest roots of classical culture. In harsh British winters, far from the Aegean homeland of Achilles and Hector, they created an artistic world that showcased their sophistication to every guest crossing the threshold.

For Irwin, who accidentally uncovered this masterpiece, the find opened his eyes to the image of Roman Britain. Thanks to this mosaic, he says, it became much more cosmopolitan than it is usually described in school textbooks — a place where global narratives lived vividly in the consciousness of the provincial elite.

As Professor Hella Eckhardt notes, this mosaic shows that myths were preserved not only in literature but also in visual traditions that artists passed down through the centuries. It reminds us that ancient stories traveled through hands no less than through words.

Today, the Ketton mosaic and the villa surrounding it are protected as a site of national significance.

Leave a comment