Caracalla ruled between 198 and 217 AD.

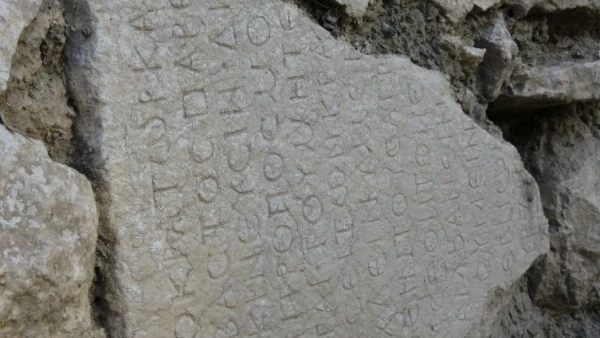

In the Turkish province of Burdur, specialists discovered marble blocks with inscriptions from a lost letter of the Roman Emperor Caracalla in an abandoned rural house. The house was initially set to be demolished, but Turkish authorities halted the decision.

According to Haber, researchers found several marble blocks embedded in the walls of the building. The Burdur museum directorate then intervened. The stones were recognized as cultural heritage objects. They are under state protection and will be handed over to the government for preservation in the future.

The farmhouse was built in the 1950s in the village of Yaryshly. Marble blocks were used in its construction, transported by cart from the nearby ancient city of Takina. Latin text from an imperial decree issued by Emperor Marcus Aurelius Severus Antoninus, better known as Caracalla, was found on ten stones. He ruled the Roman Empire between 198 and 217 AD.

Upon closer examination of the blocks, scholars noted that two stones bore the letter P, which is used in Greek rather than Latin. Additionally, the inscription ΔΗΜΗΤΡΙΟΣ (DEMETRIOS) was left in Greek.

According to researchers, the slabs were part of a public structure, such as city gates or an administrative building. They may have displayed the emperor's message to local citizens.

Takina is located on Lake Salda in the ancient region of Pisidia. The city had deep Greek roots before becoming part of the Roman Empire. It thrived under both Hellenistic and Roman rule, combining Greek civic traditions with imperial administration.

Researchers explained that displaying decrees on marble aligns with the Greek custom of leaving official messages in public places. This practice continued during Roman rule throughout Asia Minor.

Greek influence in Takina was evident in its architecture, temples, and necropolises, many of which were built in the classical style long before the Roman conquest. Under Roman rule, these cities retained their Greek character, serving as administrative centers of the empire. Inscriptions in both Greek and Latin were often created there.

A former village resident, Ferhat Agyl, recounted that the stones were brought by locals from the Asar hill, and the house was built by his father-in-law. The marble blocks were transported by cart, as only a few villagers had tractors at that time. Twenty-two years ago, the man's family received a letter from the museum requesting that the stones be preserved if the house were demolished.

The Burdur Museum Directorate confirmed that the blocks will continue to be protected until they are removed for study. Specialists plan to transfer the inscriptions to the museum for preservation and further analysis.

Archaeologists believe that the find may shed light on how imperial decrees were disseminated and displayed throughout Roman Anatolia. They hope that future excavations in Takina and its surroundings will help uncover other fragments of Caracalla's lost letter, reconstructing the complete picture of communication between the emperor and distant provinces.