They quarreled so severely that they never saw each other again for the rest of their lives.

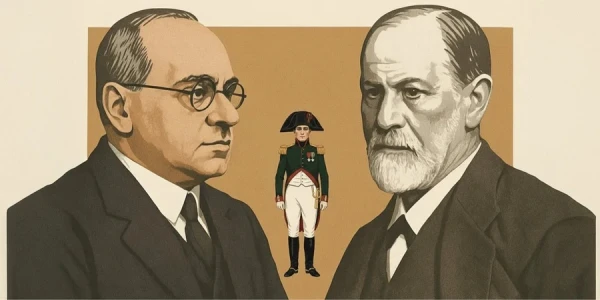

115 years ago, Austrian psychoanalyst Alfred Adler developed the theory of the inferiority complex, which is the driving force behind human development. He encountered the anger of his teacher Sigmund Freud, and then the school of psychoanalysis split into two irreconcilable camps.

It all began when in 1900, the father of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud published his book "The Interpretation of Dreams," which received mocking reviews from doctors and scholars. Freud was offended and was already close to depression when suddenly, one after another, approving articles by a certain Alfred Adler began to appear in the press. Adler wrote that Freud was misunderstood and explained in simple terms why his theory of dreams made sense.

Freud quickly found his supporter — a 30-year-old ophthalmologist from Vienna who also worked in child psychiatry. The grateful luminary invited the young colleague into his close circle, and despite a 14-year age difference, a close friendship developed between them.

Freud regarded Adler condescendingly and considered him his student until it became clear that Adler had a radically different view of psychoanalysis. And after nine years, they quarreled so severely that they never saw each other again for the rest of their lives.

In 1912, Adler published the work "On Nervous Character," summarizing the main concepts of individual psychology. In the same year, he founded the "Journal of Individual Psychology," the publication of which was soon interrupted by World War I. For two years, Adler served as a military doctor on the Russian front, and upon returning to Vienna in 1916, he headed a military hospital. In 1919, with the support of the Austrian government, Adler organized the first children's rehabilitation clinic. Within a few years, there were about thirty such clinics in Vienna, staffed by Adler's students. Each clinic's personnel consisted of a doctor, a psychologist, and a social worker. Adler's work gained international recognition. Similar clinics soon appeared in the Netherlands and Germany, and later in the USA, where they continue to operate to this day. In 1922, the previously interrupted publication of the journal resumed under a new title — "International Journal of Individual Psychology." Since 1935, under Adler's editorship, the journal has been published in English (since 1957 — Journal of Individual Psychology).

In 1926, Adler received an invitation to take the position of professor at Columbia University in New York City. In 1928, he visited the USA, where he lectured at the New School for Social Research in New York. As a staff member of Columbia University, Adler spent only the summer months in Vienna, continuing his teaching activities and treating patients. With the rise of the Nazis to power, Adler's followers in Germany faced repression and were forced to emigrate. The first and most famous experimental school, which taught according to the principles of individual psychology, founded in 1931 by Oscar Spiel and F. Birnbaum, was closed after the Anschluss of Austria in 1938. At that time, the "International Journal of Individual Psychology" was also banned. In 1946, after the end of World War II, the experimental school reopened, and the publication of the journal resumed.

In 1932, Adler permanently moved to the USA. In the last years of his life, he actively engaged in lecturing at many higher education institutions in the West. On May 28, 1937, while visiting Aberdeen (Scotland) to give a series of lectures, he unexpectedly died of a heart attack at the age of 67. He was buried in Aberdeen.

Alfred had four children: Valentina (1898), Alexandra (1901), Kurt (1905), and Cornelia (1909). Alexandra and Kurt became psychiatrists like their father. Valentina was an activist of the Comintern, worked at the Foreign Workers Publishing House in Moscow, and was repressed for supporting Trotskyism. His granddaughter is journalist Margo Adler.

Leave a comment