"His image, his popularity, his unrestrained language were like a bone in the throat."

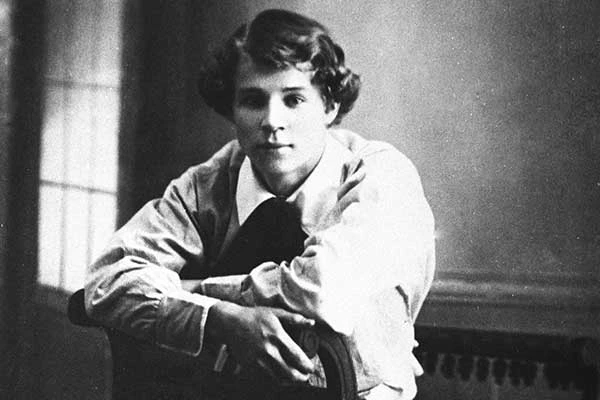

The reading humanity marked the 130th anniversary of the birth of the great Russian poet Sergey Esenin. His poems are read and reread by generations, they have been translated into 150 languages, numerous musical works have been written based on them, and his fate has been recreated multiple times in film and on stage. A conversation about the life and work of Esenin with poet and publicist, laureate of literary awards Yuri Kublanovsky.

— Yuri Mikhailovich, over the years among your favorite poets you have mentioned Pushkin, Mayakovsky, Pasternak, Akhmatova, Khodasevich, Mandelstam, Zabolotsky, Brodsky. But it seems you did not mention Esenin in this list. Although, it seems to me, he should be close to you with his acute love for Russia.

— I see you decided to take the bull by the horns right away? Well, I will answer directly: I love and appreciate many lines, stanzas, and other poems of Esenin: "Song of the Dog," "I do not regret, I do not call, I do not cry," "Goodbye, my friend, goodbye," the poem "The Black Man." However, my love for his poetic world as a whole is hindered by his persistent emphasis on his "hooliganism" and "scandalousness." I am a peaceful person, and any anarchy repulses me, drunken scandals — disgust. All this astonishingly combines in Esenin's lyrics with piercing tenderness and aching love for nature, for people — that is what resonates with me. And his sense of Russia, of the homeland, is hardly comparable to that of his contemporaries, except perhaps for Blok. With Blok, he is also connected by flashes of nihilism, which sometimes roughen his work.

— Much is written and said about the antagonism between Mayakovsky and Esenin — the main figures in Soviet poetry of the 1920s. The former was known as an avant-garde poet, a proponent of "poetry of the future," while the latter was considered a peasant singer, a supporter of traditional poetic forms. They often sparred with each other. Esenin called Mayakovsky's poems agitprop, while Mayakovsky referred to Esenin's poetry as "idealized provincialism." Were they indeed opposites or is this a false dichotomy?

— The time was such: there was a lot of music (the "music of the revolution," which Blok urged to listen to), but no less "chaos instead of music." In this mess, sometimes bloody, everyone was boiling. In his last years, Esenin wrote quite a bit of Soviet poetry, but let us not forget his dreadful lines, albeit from the voice of his double, the "black man": "This man lived in a country of the most disgusting thugs and charlatans."

No one seems to have spoken more harshly about that time. Yet Mayakovsky has piercing lyrics that touch the soul. So everything here is ambiguous.

But if I have to choose between them (although perhaps there should be no "choosing"?), then Esenin is closer to my heart, while Mayakovsky is too explosive. I remember Mandelstam highly valued Esenin's line: "Did not shoot the unfortunate in the dungeons." Such poetry required not only talent but also fearlessness. And what splendid images Esenin has in the same "Black Man"! "And the trees, like horsemen, gathered in our garden" — you can almost see the snowy, enchanted arcs of branches under the moon outside the window. Here it is, our national Russian metaphorical poetry.

— I would still like to clarify Esenin's attitude towards the October Revolution. It seems he initially welcomed it warmly, though "more spontaneously than consciously" and "with a peasant inclination," but after a trip abroad in 1923, under the influence of white émigrés, he allegedly came to reject the revolution and Soviet power. Is this true? For example, the pathetic "Ballad of Twenty-Six," written by Esenin in 1924, which asserts that "communism is the banner of all freedoms," does not quite fit this interpretation.

— I have already touched on this topic, but I must return to it. In Esenin, disgust for bloodshed coexisted with a yearning for anarchy. This is generally in the Russian national character: let us recall, for example, Shukshin's irresistible sympathy for Stenka Razin, who embodied the element of rebellion. Esenin, I would say, had a convulsive relationship with the revolution and its development, which changed from year to year, if not from month to month. And it seems to have drifted towards acceptance. And, evidently, not only for pragmatic reasons. He grew tired and began to strive for an orderly and, as it seemed to him, just life. Although I am convinced: in any case, under Soviet power, he would not have survived.

— "Religious doubts visited me early," Esenin confessed. "In childhood, I had very sharp transitions: sometimes a period of prayer, sometimes extraordinary mischief, up to blasphemy." What were his relationships with religion, with Orthodox faith in his mature years, in your opinion?

— "And do not teach me to pray. No need! There is no return to the old," he wrote in 1924 in his brilliant "Letter to Mother." These verses, with their inexhaustible heartfelt quality, are comparable to Pushkin's verses to his nanny. The awakening of religious consciousness in a person is unpredictable. However, the current life did not predispose to religiosity — both due to the wild nature of Esenin and the atheistic poison of the surrounding life, which had tightly sealed the pores of culture and everyday life. There were, of course, exceptions: Orthodoxy flickered in the folk depths, but it is unlikely that Esenin could have grasped it.

— As already mentioned, Esenin drank a lot, caused scandals, was repeatedly arrested, and had 13 criminal cases opened against him, but he left behind a significant creative legacy that barely fit into seven volumes and nine books of complete works. How does one reconcile this with the other?

— "If you only knew from what garbage poems grow, without knowing shame," Anna Akhmatova confessed. What is there to be surprised about? Esenin wrote as he breathed; it seems the poems spilled onto the paper by the very nature of his being — without a serious associative spectrum, the result of diligent cultural pursuits. By the way, let us recall that Blok drank no less than Esenin; drunkenness was his illness. And yet he wrote a great deal. Poetic productivity is an unsolvable mystery, connected with such a changeable matter as inspiration.

— In a conversation with his longtime friend, "the first Moscow dandy" Anatoly Mariengof, Esenin boasted that he had 3,000 women, then reduced this number by ten and even a hundred times. In reality, seven or eight of his married and unmarried wives are known. Among them are Anna Izryadnova, Zinaida Reich, Isadora Duncan, Galina Benislavskaya, Sofia Tolstaya, with each of whom he, however, did not live long. Did he have bad luck with women, or, on the contrary, did women have bad luck with Esenin?

— I’m sorry, but it’s delicate to discuss this. I didn’t delve into the details, but it seems there were manifestations of cynicism, vulgarity, and rudeness on his part. Thank God, this almost never made its way into his lyrics. Esenin is one continuous self-contradiction. But his tangled personal life is not our business.

— However, we cannot avoid discussing the topic of the poet's suicide. Or was it murder, as, for example, writer Vasily Belov insisted, and later the baton was taken up by the father and son Kunyaev and others. Various versions circulate in the press regarding this matter. In particular, it is claimed that Trotsky might have been behind the poet's murder, who allegedly hired the Chekist Blumkin for this role, or even the full might of Soviet power. Zakhar Prilepin, who wrote a book about Esenin, considers the version of the poet's murder untenable. What is your opinion on this dramatic plot?

— Attempts to unravel the mystery of Esenin's demise still largely carry, so to speak, an ideological character. Esenin's life was generally studied by people of a patriotic orientation. Some of them are convinced that the poet was killed by Trotskyists, Bolshevik foreigners, who were brought to the surface of political life in countless numbers by the revolutionary tide. For the new rulers, Sergey Esenin, his image, his popularity, his unrestrained language were like a bone in the throat. Others, fanatical supporters of the revolution and Bolshevism, cannot even imagine tainting Esenin's robes with suspicion of his violent death at the hands of the Chekists.

— After his death, whether voluntary or violent, Esenin was labeled a kulak, petty-bourgeois poet by Bukharin and banned for several decades. However, his poems were passed down orally, circulated in manuscripts, and had a significant influence on several generations of Soviet poets. Is the Esenin tradition felt in contemporary poetry?

— The Esenin tradition is primarily that part of his passionate heart that he invested in his poetry. It is not a school, not a literary technique. I believe that anyone who feels Russian poetry as a special spiritual phenomenon, and not just as mere verbal art, cannot help but turn to Esenin again and again.