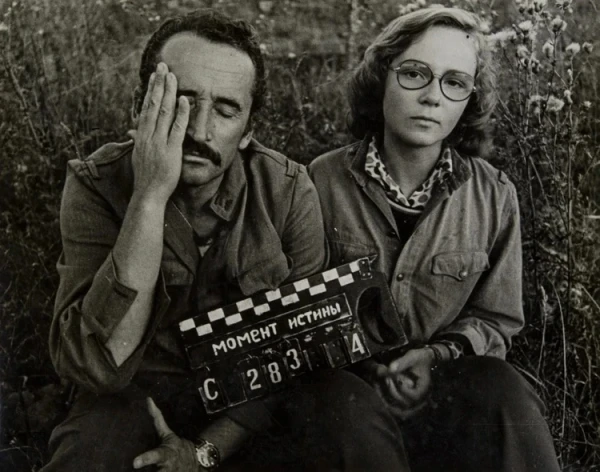

In the lead role, I can be famous Sergey Shakurov.

Recently, the film "August" was released, based on a cult Soviet novel. We recall how the book was attempted to be brought to the screen for the first time.

Vladimir Osipovich Bogomolov wrote his works slowly. The novella "Ivan," which became the basis for Andrei Tarkovsky's "Ivan's Childhood," was published in 1957. The next novella, "Zosya," came out only in 1963. And "The Moment of Truth," which became one of the most famous Soviet novels, was published in 1974: Vladimir Osipovich had been writing it for more than twenty years. In any case, as early as 1951, he made a note: "I intend to write an adventure novella for youth. The theme is old, but the novella will be new." In 1964, another note appeared: "The action is expanding and increasingly occupies my thoughts. Roughly 22 sheets have been completed" (this is over 500 typewritten pages). But it was only in the early 70s that Bogomolov began discussions about publication in the magazine "Youth," referring to the novel as "a small detective story."

It is said that the text was initially feared to be published. A friend of the writer, Eduard Polyansky, published an essay about him after his death; it states that the manuscript from the "Youth" editorial office was immediately sent to the KGB, and one general "really liked the novel. He... stole the manuscript. He took it to his dacha and locked it in a safe. That’s how a precious item in a single copy is kept. Bogomolov was furious. 'I will sue your general!' he shouted over the phone. The manuscript was returned. It was then that the writer saw all the wonderful recommendations from the KGB. In the novel, a general gasping for breath from asthma cannot sit down: there is no chair. The KGB censor is furious: 'Is there no chair for a Soviet general? Put one!' In another part of the novel, soldiers discuss the inaccessibility and finickiness of Polish ladies, reminiscing about their own: our Dunya is a different matter, pour her a hundred grams - and she's ready. The general ominously noted in the margins: 'Who gave the author the right to speak of our Soviet Dunya like that?!' The manuscript was riddled with directives. It was not just one general working on it: there were about a dozen different handwriting styles in the margins..."

Moreover, it is said that the chief editor of "Youth," Boris Polevoy (author of "The Tale of a Real Man"), and his deputy Andrei Dementyev (a famous poet, author of many song lyrics) planned to cut at least two chapters from the novel: "At the Headquarters of the Supreme Commander" (they categorically disliked how Stalin was portrayed and his presence in the text in general) and "In the Barn" (the one with the asthmatic general). Bogomolov, in indignation, sent a telegram to "Youth" expressing his distrust of the magazine and asking them not to publish his book. And - contrary to what Polevoy and Dementyev expected - he returned the already paid advance of over a thousand rubles (a considerable sum in Soviet times).

In any case, in October 1974, the first third of the book was published in another magazine - "New World." Under the title "In August 44..." and without any edits from the editors or KGB staff. (The title "The Moment of Truth," which later seemed to the writer the best and final, appeared when the magazine was already being typeset - and supposedly Bogomolov was told that if they fiddled with his approval, the publication would be delayed).

Long or short, the novel was published. And it became a sensation. Critic and reviewer of "Komsomolskaya Pravda" Denis Gorelov wrote: "Bound from three notebooks of 'New World' under a cloth cover with gold embossing, Bogomolov's novel instantly became iconic, a must-read for elite readers alongside 'Joseph and His Brothers,' 'A Bomb for the Chairman,' 'The Gulag Archipelago,' and the now blissfully forgotten 'Altyist Danilov.' This was the first book that my father brought as a rite of passage into adolescence. (...) Millions of city dwellers held deeply personal images of Alekhin-Tamancev-Blinov, Mishchenko, Captain Anikushin in their minds.

"Bogomolov 'buried' the film with his own hands"

Vladimir Osipovich was one of the most enigmatic Soviet writers. It is known that he hated being photographed: upon seeing a camera, he would turn away or cover his face with his hands, resulting in very few photographs of him. He received journalists, spoke with them sometimes several times, but could prohibit the use of a tape recorder. This happened with Olga Kuchkina, a reviewer for "Komsomolskaya Pravda": she recorded conversations with the writer from memory immediately after meetings, and a year after his death, she published an essay titled "The Victor."

Then she read with astonishment letters in which people who knew Bogomolov in his youth left no stone unturned from what he had told. One of his friends claimed: "He is a fantasist. He was a talented person. He began writing about the war and identified himself with his heroes. He invented himself. A person has the right to invent himself! I consider it a feat to invent a person!" In general, it turned out that the front-line soldier and hero "invented his biography. A squad commander, deputy platoon commander, orders, medals - none of this existed."

In fact, almost any detail related to Bogomolov and his novel, when checked, is puzzling. For example, one can encounter a lot of claims that "The Moment of Truth" is based on real events, that the characters have prototypes, and that the author worked in archives for weeks, months, years. But Vladimir Osipovich himself initially wrote to Boris Polevoy that all events and characters in his book are fictional, and that archival materials or closed sources were not used... And who to believe?

The story of the film adaptation of the book, which in 1975, immediately after publication, was undertaken by the famous Lithuanian director Vytautas Žalakevičius, also seems incredible (and incredibly convoluted). He invited Sergey Shakurov to play Alekhin, Anatoly Azo to play Tamancev, and debutant Alexander Ivanov to play Blinov. He nearly finished shooting when two sad events occurred. First, actor Bronys Babkauskas, who played General Egorov, committed suicide. Secondly, Bogomolov saw the filmed material.

He disliked everything. And the fact that "Žalakevičius inexplicably made the actors not shave for a week or more, filmed them with stubble on their faces, with sleeves rolled up above their elbows, without belts, with tunics unbuttoned to the navel. They... looked like prisoners from the guardhouse." And that "in all the material, the director had implemented a westernization: the heroes moved and spoke like cowboys in 'The Magnificent Seven.' And, of course, that the director 'does not understand... has not fought... is not in the subject...'

In the end, as film director Boris Krishtul recalled a few years ago in an interview with film scholar Alexander Fedorov, Bogomolov said he would "step aside," would not be credited... As a farewell, he threw out - "In general, do what you want..." In short, they parted calmly. An unprecedented precedent for the USSR! But on December 5, 1975, a meeting of the Moscow City Court took place, and it ruled: "Suspend the film production and do not conduct any filming without the author's consent."

Krishtul recalled: "Of course, the death of the wonderful Lithuanian actor Bronys Babkauskas was a heavy blow for the filming crew, but our film perished not because the actor was gone - the living picture of the talented director was 'buried' by the outstanding writer Vladimir Bogomolov with his own hands. About two weeks after the court, a special meeting of the secretariat of the Union of Cinematographers of the USSR took place, at which eminent directors pompously branded Bogomolov and defended their colleague, Žalakevičius. But even the Secretary-General of the UN could not change the author's position. Two years later, the money was written off as a loss for the film studio, and the last hope that Bogomolov would come to his senses faded..."

The film footage was simply washed away, that is, destroyed. However, Fedorov asked Krishtul with timid hope: "There are several versions that the boxes with the precious materials of 'The Moment of Truth' may still be stored somewhere. Could that be?" The answer was vague: "They say that except for N.V. Gogol, manuscripts do not burn..."

Film scholar and cultural expert Mikhail Trofimenko, who personally knew Žalakevičius, now writes: "Vitas recalled how, to console him, the KGB issued him an all-inclusive voucher to the best Sochi hotel and provided two officers for escort (they lived in some separate chamber), so that the director wouldn’t do anything to himself in despair. The fears of the Chekists were evidently fueled by the suicide of the great actor Bronys Babkauskas right during the filming."

And Konstantin Ernst, one of the producers of the film "August," who communicated a lot with Bogomolov in the last years of his life, says: "I remembered his sad experience with Vytautas Žalakevičius, I asked about it, he replied that the latter made a film about the 'forest brothers,' which is why he was against it. The great film by Žalakevičius 'No One Wanted to Die' was dedicated to the struggle against the 'forest brothers,' and Bogomolov believed that it was the same here. Unfortunately, we will never see the film based on 'The Moment of Truth' that Žalakevičius shot, but he was an outstanding director, and at his best, and I think it was talented cinema."

Leave a comment