He obtained a Russian passport under the name German Bazhenov and lives under the protection of the FSB.

One of the most wanted fraudsters in Europe, former Chief Operating Officer of the bankrupt German payment system Wirecard Jan Marsalek, turned out to be an investor in Libyan cement assets, according to an investigation by The Financial Times. In 2024, a private deal was concluded in London for the sale of Marsalek's shares with partners in three cement plants of the Libyan Cement Company to a businessman linked to General Khalifa Haftar. He is considered the ruler of eastern Libya and a long-time partner of Russia.

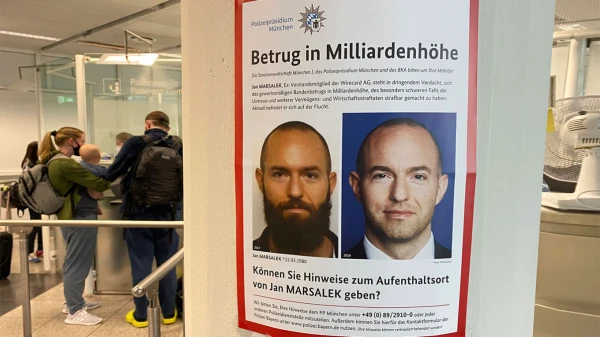

According to Süddeutsche Zeitung, Marsalek, who fled arrest in 2020, obtained a Russian passport in 2021 under the name German Bazhenov and lives in Russia under the protection of the FSB. He previously boasted about trips to Palmyra in Syria "to visit Russian military" and helped establish the presence of the Wagner Group in Libya.

Before selling the shares of the plants, Marsalek had been investing in Libyan projects for years through a network of offshore structures in Cyprus, Dubai, and the Isle of Man and nominal owners. The FT notes that a protracted corporate conflict has unfolded around the Libyan cement plants and associated companies between Marsalek's former partners, which will now be considered in British courts. According to FT sources, Marsalek's investments in Libya, had he retained control over them, would now amount to tens of millions of dollars. He also had other projects in Libya — he owned companies that leased drilling rigs.

The Financial Times cited another Libyan episode from Marsalek's life. In 2018, he proposed to one of his Libyan partners, Ahmed Ben Halim, and his associates to invest in a new token Toncoin, which was being launched by the Telegram platform. Its founder Pavel Durov met Marsalek and invited him to join the project. A separate fund was created for Libyan investors; however, Credit Suisse, which was facilitating the sale of the tokens, blocked the transaction. It turned out that the bank was willing to accept Marsalek's money (his involvement in the Wirecard financial fraud had not been disclosed), but was concerned about his connections in Libya.

To circumvent banking checks for money laundering, the investors decided that the funds would be invested by Marsalek in his name but at their expense. However, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission blocked the issuance of the Telegram token, and Marsalek was forced to return the money to the Libyans.

Leave a comment