Official Berlin is shifting towards conservatism.

The far-right party "Alternative for Germany" has become one of the main problems for its democratic competitors on the German political landscape. After the extraordinary parliamentary elections in February 2025, it doubled its presence in the Bundestag, performed quite successfully in the regional and European elections of 2024–2025, and currently holds the first or second rating in the country — depending on the poll.

In May of this year, the AfD was recognized as right-wing extremist based on a decade-long observation by the intelligence services, but this did not significantly affect its ratings.

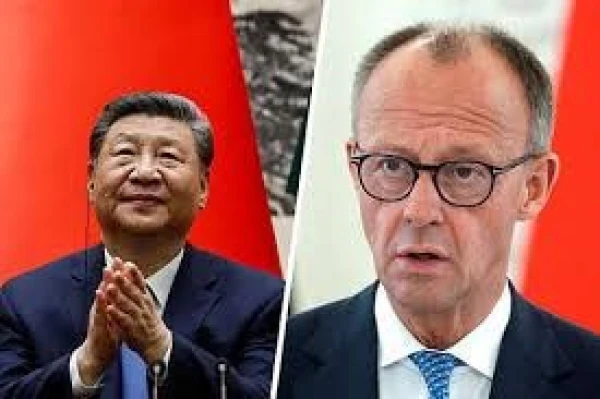

In this context, the Chancellor of Germany, Friedrich Merz, has initiated a new round of verbal attacks on the "Alternative," which are much harsher and more intense than in the past. Why did Merz decide to adopt such a strategy and what lies behind his rhetoric? This is discussed by political scientist Dmitry Stratievski, who lives in Germany.

"Right of the CDU/CSU"

In debates about the "right flank" in Germany, the words of Franz-Josef Strauss, a luminary of German politics who held a good half of the significant positions in the country during his long career, from ministerial posts to the premiership, are often cited: "There should be no democratically legitimate party to the right of the CDU/CSU." However, it is not always given enough attention that Strauss did not desire such a situation but did not exclude it either. And if for more than half a century this formula was adhered to, with the far-right absent from the Bundestag and the role of "even further right" being played by right-conservative currents within the Christian Democrats, then in 2017, with the AfD entering the Bundestag, the previous balance of power became a thing of the past.

Since then, the CDU and its Bavarian ally, the CSU, have been forced to enter direct competition with the "Alternative" for the votes of right-wing conservatives. This refers to those who would like, compared to the proposals of centrists and "classical" conservatives in the "German variant," some tightening of the course, for example, on migration and security issues, but still had certain reservations about voting for radicals. The greatest outflow of votes for the Christian Democrats occurred at the end of Angela Merkel's tenure. In the first decade of Merkel's tenure as head of the cabinet, the degree of discontent from the right-conservative flank regarding her "too left" policies had not yet reached boiling point, and the CDU won elections thanks to the popularity of its leader. But after Merkel left the political arena, her close associate and successor Armin Laschet suffered a crushing defeat in the first elections, showing the worst result for conservatives in the history of the Federal Republic of Germany and paving the way for Social Democrat Olaf Scholz to the chancellorship.

Friedrich Merz, who once had to leave big politics due to ideological and personal conflict with Merkel, upon his return became the head of the CDU under the slogans of returning to traditional German center-rightism of the Helmut Kohl era. Observers began to speak in this regard about the "reactivation of neoconservatism," and Merz himself, speaking about his vision of the role of the CDU in modern Germany, called the synthesis of conservative, liberal, and Christian-social elements as key. But, to generalize and translate into the realm of political practice, "anti-Merkel" became his informal motto almost to the same extent as "anti-Biden" for U.S. President Donald Trump.

To win the 2025 elections, Merz chose a dual strategy. On the one hand, he firmly distanced himself from the far-right in general and from the AfD in particular. In February, shortly before the elections, the chancellor candidate at his party's congress once again clearly emphasized the possibility of cooperation with the "Alternative":

We will not cooperate with them. We will not tolerate them. Nothing will happen!

On the other hand, Merz made a rather sharp "turn to the right" in his rhetoric, trying to win the sympathies of the undecided. And not only in rhetoric. In January 2025, the CDU/CSU faction presented a package of measures to tighten migration legislation, residence rules in Germany, and deportation procedures to the Bundestag. It was adopted solely thanks to the votes of the AfD.

In an interview with the first channel of German TV, the future chancellor firmly rejected accusations of cooperation with the "Alternative":

If someone puts a proposal to a vote, and other parties support it or not, that is not called cooperation.

Formally, Merz is right. The AfD is represented in the Bundestag, state parliaments, and hundreds of councils of small and large regions and municipalities, voting daily, say, for road construction or building repairs. Democratically elected deputies cannot be prohibited from voting at their discretion. But Merz was being disingenuous: it was precisely on this bill that he would not have been able to obtain a different majority in the then parliament and deliberately relied on the support of the AfD on a key political issue for them.

Merz's gamble paid off. He won the elections, became the head of the government of the Federal Republic of Germany, and achieved the inclusion of measures for border protection and easing the deportation of foreigners deprived of the right to stay in Germany in the coalition agreement with the Social Democrats.

Much of what was agreed upon has already been implemented. But despite the active PR of his own actions and the slogan "migration turnaround," Merz's personal rating, as well as that of his party, began to decline. In the summer, the party was gaining 3–4 percentage points less in nationwide polls than in the elections in February. The rating of the Christian Democrats continued to decrease in nine out of 16 federal states.

At the beginning of October, only 27% of respondents were satisfied with Merz's work, down from 33% in September and 38% in May. Merz began to lose the electorate from various political camps. For staunch opponents of migration, he is "too soft," while the chancellor himself is not ready, by his own convictions, to pursue an even more right-wing policy, especially in coalition with the Social Democrats. The AfD is deliberately raising tensions, accusing Merz of a false struggle against illegal migrants and presenting itself as the "true defenders of the safety of Germans," not hesitating to manipulate the number of asylum applications.

The chancellor has lost popularity even among supporters of a more moderate course, such as the social-liberal wing of the Christian Democrats, or voters who are willing to vote for either the CDU or the SPD depending on the circumstances, as was the case during Merkel's time. For this group, Merz is already associated with a violation of the foundations of humanism and the protection of human rights, leading to distrust.

The rating of the AfD, on the contrary, has grown in all 16 federal states without exception compared to the results of the February elections and reached record levels in five eastern German regions, from 34% in Brandenburg to 40% in Saxony-Anhalt. Something urgently needed to be done about this.

Attack to Win

For Merz, the sympathies of right-wing conservatives once again became crucial, thanks to which, according to many sociologists, he won the elections to the Bundestag. Convicted far-right "fans" of the AfD have already distanced themselves not only from the Christian Democrats but from democracy as a whole, so it would be unwise to count on their votes. At the same time, during the "rightward shift" in all German politics, including among the Democrats, there has been a kind of de-tabooing of the "Alternative." Previously, the right-conservative voter was not ready to vote for a party proclaiming slogans on the edge, or even beyond the edge of morality and even current legislation, and, "gritting his teeth," cast his vote for the CDU. Now, however, the right public debates have largely "normalized" the AfD and made support for this party something quite "ordinary" and no longer reprehensible. And Merz has decided to act again on a dual principle.

On the one hand, the chancellor allowed himself to make a highly problematic statement. In response to a journalist's question about the government's efforts to reduce the number of illegal migrants, Merz replied:

In the migration issue, we have made significant progress. In this federal government, we have reduced the numbers between August 2024 and August 2025 by 60%, but, of course, we still have this problem in the appearance of cities.

The phrase "appearance of cities" instantly became a catchphrase and provoked a storm of emotions in society. The left, centrists, and human rights activists accused Merz of using far-right rhetoric and almost of racism. A massive protest demonstration took place in Berlin, where Bundestag deputies from the SPD were spotted, including the deputy chairman of the faction, a party that is part of the ruling coalition with the CDU/CSU. Conservatives applauded the chancellor for his "candid words," while the AfD (this time unsuccessfully) tried to accuse Merz of insincerity and an attempt to "divert attention." But the statement achieved its goals: the chancellor's rating and that of his party rose, with 73% of respondents supporting his words.

In conjunction with new data on a 20% increase in deportations since the beginning of the year, this produced the desired effect.

On the other hand, Merz sharply intensified his criticism of the AfD, even more actively drawing a line between his party and the far-right and trying to strike at their sore points. The chancellor emphasized that the "Alternative" has nothing to do with conservatism, while far-right parties in Europe (German ones included) prefer to deny their radicalism, calling themselves "national conservatives." The chancellor also proclaimed "the harshest resistance" against the AfD.

Once again denying any cooperation with the far-right and openly calling them "extremists," the head of the cabinet pointed out the "absence of points of contact" with them:

We are divided not by details but by fundamental issues and fundamental political beliefs. <…> The AfD questions not only the decisions of the last 10 years but also the basic principles on which the Federal Republic of Germany was built in 1949.

Karsten Linnemann, the general secretary of the CDU, does not lag behind his boss:

It is becoming increasingly clear that the AfD simply wants a different country. It is not inclined to seek solutions. It exists on problems. It divides society.

In fact, Merz and Linnemann, a close friend of the chancellor and a representative of the influential intra-party business lobby, made sensational statements for conservatives that could previously be heard only from social democrats and the left. They are not just criticizing the AfD once again but are effectively directly accusing the party of unconstitutional activities and threats to the democratic and legal foundations of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Such accusations are also consistent with the statements of two politicians, the Minister of the Interior of Thuringia, Georg Meyer (SPD), and the chairman of the Bundestag committee for oversight of the intelligence services, Markus Henrichmann (CDU). They informed the public that AfD deputies submitted 47 requests regarding the state of critical infrastructure within just one year, from water supply, transport communications, and population protection plans in crisis situations to police and intelligence agency equipment, the possibility of using drones, and cybersecurity. Representatives of the governing parties made it clear that such a significant number of specific requests paradoxically coincides with what might interest Russia.

Politicians and journalists began to speak of "serious accusations" and "suspicions of espionage."

Ban on the AfD?

There is no doubt that Merz is now seriously tackling his main competitors on the right flank. He uses Strauss's formula and makes it very clear to voters: true conservatives are the Christian Democrats, while those who are even further right are extremists and are outside the democratic spectrum. Merz's strategic task is to return the electorate to the situation of 2018–2019, when the AfD was already a significant party with representation in parliaments and a double-digit rating but still had a somewhat marginal image as a mouthpiece for convinced far-right individuals and "disillusioned" voters, predominantly from the east of the country.

In this duel, Merz consciously raises the stakes, not only sharpening the rhetoric against the "Alternative" but also using once-typical far-right speech patterns and images that would have been unimaginable coming from not only Merkel but even Kohl.

It is possible that the new round of confrontation between the democrats and the AfD has much more significant goals than just raising the CDU's rating and winning over the right-conservative electorate. After the party was assigned the status of "guaranteed right-wing extremist," debates in society about banning the "Alternative" due to its unconstitutional activities, undermining German statehood, and the foundations of democracy have not ceased. In the previous Bundestag session, signatures were already being gathered to file a lawsuit with the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany, the only institution that can make such a decision, but there were too few.

At that time, representatives of various parties feared the failure of the lawsuit due to a lack of evidence, which could only strengthen the far-right. In the new situation, where the "right-wing extremist status" of the AfD provides law enforcement with special powers to monitor the party's structures and individual officials, including using special means, new confirmations of threats from the "Alternative" could be disclosed, from possible espionage and foreign funding to prohibited slogans and calls. This could give more optimism to Bundestag deputies and lead to a lawsuit demanding the ban of the AfD. It is possible that this is the last parliamentary session where this can be done at least arithmetically.

Leave a comment