This experiment was proposed to be conducted in the USSR in the 1980s.

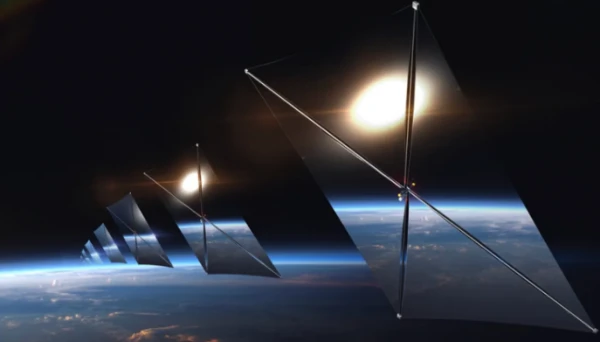

The American company Reflect Orbital plans to create a constellation of 4000 giant mirrors in low Earth orbit to "sell sunlight" at night. The launch of the first device is scheduled for early 2026. However, experts consider this plan extremely impractical and even dangerous to human life.

Concerns about the increasingly sprawling group of Earth-orbiting satellites and the consequences that new launches may bring have recently been voiced with alarming frequency. For instance, they are already starting to interfere with astronomical observations, and the risks of large-scale accidents are growing at an incredible rate.

However, a new type of satellite is soon expected to appear, which will intentionally direct sunlight to the Earth's surface at night.

Previously, the American startup Reflect Orbital announced plans to create a constellation of 4000 giant mirrors in low Earth orbit to "sell sunlight" to customers at night. They will measure approximately 10 to 55 meters on each side. A prototype mirror named Earendil-1, about 18 meters long, could be launched as early as April 2026, according to the company's application to the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC). But it had a Soviet predecessor.

What Happened to the "Banner" Project?

It emerged in the late 1980s as part of efforts to develop solar sails—structures that use solar radiation pressure to propel spacecraft. Later, however, the technology was redirected for terrestrial needs: lighting remote areas, assisting in emergencies, and saving energy. A key figure in the project involving space mirrors was the outstanding designer Vladimir Syromyatnikov. In his view, they could illuminate the fields of Siberia, allowing for round-the-clock crop cultivation, or assist rescuers in disaster zones where electricity is unavailable.

There were two experiments in total—successful "Banner 2" and failed "Banner 2.5."

In the first case, a 20-meter-wide solar mirror was launched aboard "Progress M-15" from the Baikonur Cosmodrome on October 27, 1992. The reflector was successfully deployed on February 4, 1993. It created a bright spot (eight kilometers wide) that crossed Europe from southern France to Western Russia. It had a brightness approximately equivalent to a full moon. The experiment lasted about five hours. After that, the device was deorbited and burned up in the atmosphere over Canada. The experiment was declared technically successful, although there were certain issues. For example, the reflected light turned out to be much weaker than expected and too diffuse to illuminate a large area on Earth.

Nevertheless, the success of the first test inspired further developments. The new mirror was supposed to be perceived from Earth as five to ten full moons in brightness and create a trail about seven kilometers in diameter. However, it failed: on February 4, 1999, the experiment was prematurely terminated due to an error in the automatic control program of the transport spacecraft. As a result, "Progress M-40" was deorbited and sunk in the ocean along with the reflector.

A third project, "Banner 3," was planned, but the failure of the previous experiment led to its cancellation and the winding down of the program: the budget ran out, and investor interest waned.

Mirror Satellites: For What Purpose?

Reflect Orbital plans to launch thousands of satellites with reflective panels—essentially, giant space mirrors—into low Earth orbit to redirect sunlight to the night side of the planet.

According to the company, it could be used to power solar power plants, assist in search and rescue operations, and even combat seasonal depression by allegedly extending daylight. Reflect Orbital has already applied to the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) for a license. It intends to launch its first satellite as early as early 2026, directing sunlight to ten points as part of a starting "world tour." In the future, the company plans to launch thousands of devices equipped with mirrors measuring tens of meters to reflect light onto Earth for "remote operations, defense, civil infrastructure, and energy generation."

However, experts consider this plan extremely impractical and not recommended for implementation. Moreover, in their opinion, it may pose a real danger to human life.

What's Wrong with the New Project? Light for a Few Minutes

According to Reflect Orbital's statement, by 2030 the company will provide satellite coverage that will allow directing up to 200 watts per square meter to solar power plants on Earth—a level of illumination comparable to twilight at dawn and dusk. However, New Scientist points out that according to the specifications of the first satellite listed in the documents submitted to the FCC, the amount of useful light reaching the Earth's surface will be significantly less.

John Barentine from Dark Sky Consulting, along with astronomers from the American Astronomical Society, used data from Reflect Orbital's application to calculate how much power solar energy could receive on Earth.

"For one reflector, the amount of light reaching the surface is catastrophically insufficient to power solar power plants," he says, noting that the level of illumination will be equivalent to about four full moons, which will practically yield negligible electricity generation over a large area. Previously, Monash University astronomy lecturer Michael Brown and his colleague from Leiden University, Matthew Kenworthy, estimated that for a single device with a 54-meter mirror, the reflected light would be 15,000 times weaker than midday sunlight. To meet the company's stated plans for illumination levels (20% of sunlight), 3000 such satellites would be required, and that is an enormous number to illuminate just one region.

"Another problem: satellites at an altitude of 625 km move at a speed of 7.5 km/s. Thus, a satellite will be within 1000 km of a point on Earth for no more than 3.5 minutes. That is, 3000 satellites will provide only a few minutes of illumination. To ensure at least an hour, thousands more will be needed," experts say. A space ethics specialist from Durham University, Fiona Thomson, told LiveScience that the idea is technically "defective."

"It is unlikely to come to fruition due to the complexity of engineering execution and operation in crowded orbits," she noted.

Destructive Light Pollution

Can mirror satellites be a practical way to obtain cheap solar energy at night? Probably not, experts say. However, they will certainly produce destructive light pollution.

"Even a test satellite will sometimes be brighter than a full moon. A constellation of such mirrors will be a disaster for astronomy and dangerous for astronomers: the surface of each mirror could be nearly as bright as the sun, with the risk of permanent eye damage," warned Brown and Kenworthy.

Other specialists echo this sentiment. John Barentine referred to vision safety studies conducted by physicist James Laframboise and optometry professor Ralph Chu, which warn that such large satellites reflecting sunlight could indeed damage vision, as reported by SkyAndTelescope.

Furthermore, it will complicate the study of stars, as thousands of new bright objects will race across the sky.

Impact on Animals and Humans

Research has also shown that light pollution affects the behavior of animals and plants. Astronomer Michelle Wooten from the University of Alabama at Birmingham points out that already familiar forms of light pollution—from homes, transportation, and industrial facilities—affect birds. Light directed from orbit will have the same disorienting effect as urban lighting on bird migration and may lead to their death.

But that's not all. Given that the mirror can be pointed anywhere on Earth without warning, avoiding its impact is impossible. Flashes of light can distract pilots during takeoff or landing, creating dangerous situations that pose risks to human life.

"One small company in California can, with a few million dollars and the approval of one federal agency, change the night sky for the entire world. This is terrible," says astronomer Samantha Lawler from the University of Regina.

Leave a comment