Pyrite produces sparks when struck, and it could have been brought here specifically to help start a fire.

When it comes to when humans began to use fire in any form, we have to go back a million years, to a time when there was no Homo sapiens in sight. At that time, various hominins roamed Africa – this is the term used to describe the group of primates that includes the genus Homo. Some of those ancient hominins seemed to have been able to handle fire. But what does it mean to "handle"?

Most likely, it was fire that ignited for natural reasons, and the ancestors of humans could maintain it for some time and carry it from place to place. However, when we talk about man-made fire, which is regularly kindled using special tools (for example, stones that create sparks when struck), reliable evidence of such fire has until now been dated to around 50,000 years ago.

The authors of a recent article in Nature push this date much further back, to 400,000 years ago. During excavations in southern England, archaeologists uncovered something resembling a hearth. There were no coals, ashes, or burnt bones, but there were stones with a characteristic red coating that could indicate they had been in fire.

Until recently, it was impossible to determine from such scant evidence whether it was man-made fire or the remnants of a natural fire. But now researchers have methods that allow them to understand whether fire appeared at a specific location once or multiple times, how intense it was, and what combustion products remained afterward. For example, among such products, there are usually polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and by analyzing the ratio of different hydrocarbon molecules, one can determine whether the fire was natural or human-made.

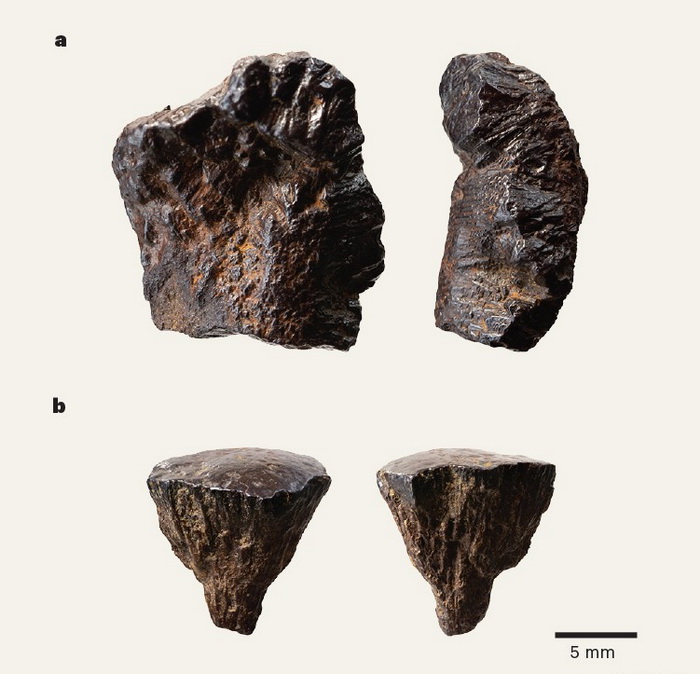

The combined data showed that the red coating on the stones was formed as a result of intense heating, and that it was much more likely to have been a campfire that burned several times, each time briefly, rather than a natural fire. The proportions of polycyclic hydrocarbons also indicated that the fire was the work of some humans. Additionally, fragments of the mineral pyrite were found nearby, which is actually extremely rare in the area where the excavations took place. Pyrite produces sparks when struck, and it could have been brought here specifically to help start a fire. Over time, it oxidizes and no longer produces sparks, but the pyrite found near the ancient hearth had oxidized after it was brought here. The age of the findings was stated to be around 400,000 years.

However, the researchers were unable to find the stones that were struck against the pyrite and on which corresponding traces remained. If such stones had been found, they would have provided clear and unequivocal evidence of the fire being man-made. Nevertheless, the collection of circumstantial evidence appears convincing enough to declare this site the oldest example of regular fire use, ignited as needed with makeshift tools. It was not Homo sapiens who kindled it, as they did not exist at that time, but most likely Neanderthals. Experts had previously suggested that fire became a common practice for members of the genus Homo somewhere between 400,000 and 300,000 years ago, and now these assumptions have been more or less reliably confirmed by this archaeological finding.

Leave a comment