"Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears. Everything is Just Beginning." Directors Zhora Kryzhovnikov, Olga Dolmatovskaya, starring Ivan Yankovsky, Tina Stojilkovich, Marina Alexandrovna, Milosh Bikovich, Fyodor Bondarchuk. Russia, 2025.

The Middle Class Stands at the Cash Registers

The Russian word "мещанин," the German "bürger," and the French "bourgeois" originally meant the same thing – "townsman." Over time, all three have sounded like accusations of banality, of self-satisfied mediocrity. The centripetal movement – from the village to the city, from the province to the capital – spawned by industrial revolutions and urbanization, has for centuries provided aristocrats, bohemians, and various rebels with their common enemy: the third estate, the urban bourgeois, the middle class.

Forty-five years ago, Vladimir Menshov's film "Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears" became a triumph both in the Soviet Union (84 million viewers, second place in the history of Soviet box office) and at the Oscars, precisely because it hit the needs of the most mass category of viewers – urban bourgeois. By making a film for them and about them, Menshov earned the grateful love of the people and the envious irritation of film snobs. "Moscow," the story of a woman who conquered the capital, was criticized for catering to the tastes, phobias, and aspirations of precisely this – the emerging bourgeoisie in megacities.

For the sugary songs of the Nikitins, for the prejudice against hereditary Muscovites from Stalin-era high-rises, and most of all for the dream of the numerous divorcees and single mothers in megacities – a moderately drinking prince-mechanic in dirty boots and with the face of Alexei Batalov. It is telling that Gosha, also known as Goga, also known as Zhora, four decades after the release, incited fierce hatred from the current revolutionaries-rebels – more precisely, rebel women. Feminists from the generation of that very Alexandra, Alexandra.

The Continuator of Menshov's Work

Menshov himself was a first-generation Muscovite. Just like Vera Alentova, who played Katerina, Menshov's wife. The director knew perfectly well for whom he was shooting – thanks to which he hit the jackpot with his second feature film: it was not a European arthouse festival that embraced "Moscow," but Hollywood, which values the combination of craftsmanship with commercial instinct above all.

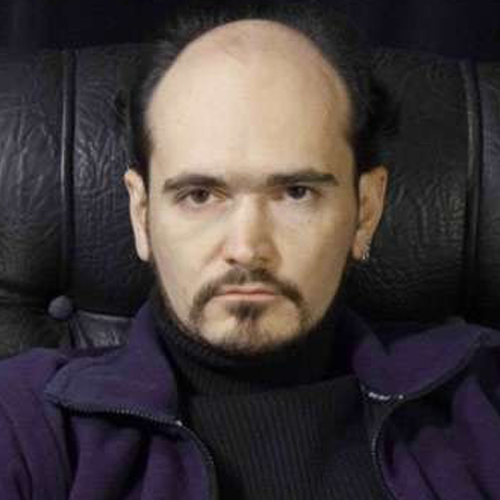

This combination has never been common on the Russian plain. Today, perhaps only the author of "Gorko!" and "The Boy's Word" possesses it in proportions comparable to Menshov's. A first-generation Muscovite whose first feature film still holds the post-Soviet championship in profitability ("Gorko!" earned 18 times its budget).

Entrusting the remake of a popular superhit to the most popular director in the country, Zhora Kryzhovnikov, seemed as logical as choosing a serial format: after all, the original two-and-a-half-hour "Moscow," whose action spans 20 years, had a steady pace. At the same time, the fairy tale of conquering the capital was turned into a musical – which is also understandable, given Kryzhovnikov's successes in this genre: both "The Best Day" and "Ice-2" achieved excellent box office.

Dreamy, Lively, and Correct

Of course, calling it a remake is a stretch: since the time of the "Olympics-80," the realities have changed so much that the old plot is stretched over them with difficulty. But the overall framework and main plot roles were preserved – fortunately, they had a universal, archetypal character in Menshov's original. In Kryzhovnikov's version, good girls, the cherished friends, also seek happiness on the banks of the Moscow River: dreamy, lively, and correct. And just like in the first half of the story, they are about twenty (the action takes place in 2003), and in the second – about forty (in 2023, respectively). Kryzhovnikov did not try to make mature matrons look like yesterday's schoolgirls: in the series, each of the three main female roles has two actresses – for example, the dreamy Ksyusha (who replaces Katerina-Alentova here) is played in her youth by Serbian Tina Stojilkovich, and in her mature years – by Marina Alexandrovna.

It should be noted that the Russian series "Breathe," which was released simultaneously with the new "Moscow," featuring the same Alexandrovna in the lead role, attracted much more attention from critics and received much more praise. The general audience also met the "Moscow" remake without the expected enthusiasm. The multi-part musical not only did not repeat the grand success of the feature original, nor did it explode on social media like the director's previous series – it even failed to make it into the main television hits of the season.

The reason for this is partly the new "Moscow" itself, made not exactly poorly, but rather carelessly, "on autopilot," and partly the historical and social context. Vladimir Menshov sang a hymn to the Soviet middle class when this class, accumulated during the calm years of stagnation in cities (by 1980, two-thirds of the country's population lived there), was numerous and united, with common aspirations and common heroes.

And what is the Russian middle class like now? There was such a class, accumulated during the "neo-stagnation" of the 2010s – now a good third of it is in Tbilisi, Riga, Berlin, some are sitting at home on donations from FBK, some are teaching "Conversations about Important Matters," while former proletarians and declassed individuals, who earned on the war, are coming up from below.

There is no stability in the world, as was said in the classics.

Leave a comment