If the Belarusian leader had come to power, the entire history of the USSR could have been different.

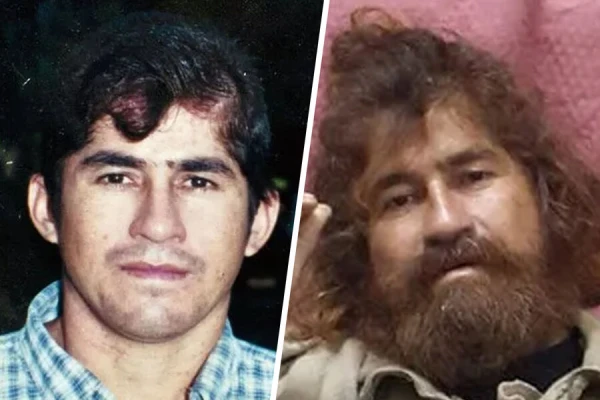

45 years ago, the most likely successor to Brezhnev was buried. A car accident cut short the life of one of the most extraordinary and promising Soviet politicians, at that time the head of the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic, Pyotr Mironovich Masherov. A Hero of the Soviet Union and a former partisan, Masherov was loved by the people: long before the perestroika politicians, he communicated with ordinary people, tried to defend the interests of the republic, and even allowed himself to disobey Moscow. This is why many still believe that the car accident was staged to eliminate a man capable of fighting for high positions in the Kremlin.

On that day, driver Nikolai Pustovit, after a sleepless night, was transporting five tons of potatoes from Zhodino to Minsk in a dump truck. He was very sleepy, but he tried to stay awake by inhaling air from the slightly open window. About 50 meters ahead of him was a MAZ truck. Sleep was increasingly pressing on Pustovit, his attention waned, and his reaction dulled. Suddenly, the truck in front began to slow down. At that moment, Pustovit was distracted from driving to check the instruments, so he noticed the dangerous maneuver too late. Trying to avoid a collision, he sharply turned the steering wheel to the left.

The truck veered into the oncoming lane, and the black "Chaika" had no chance of avoiding a collision. The terrible impact caused the dump truck's fuel tank to explode and a fire to break out. The driver was thrown from the cabin along with the door that flew off. He caught fire, and he survived only thanks to the bystanders who rushed to help.

A horrifying scene lay before them. In the middle of the highway, a wrecked luxury sedan smoldered, covered in potatoes. The head of the Belarusian SSR, Pyotr Masherov, his driver, and a security officer were already beyond saving.

Pyotr Masherov was the first leader of Belarus born during the Soviet era (in 1918) and one of the few among officials of such a level who truly fought in the Great Patriotic War. In August 1941, he escaped captivity by jumping from a train bound for Germany and soon began organizing underground resistance in the territories of the Vitebsk region occupied by the Germans, and later in neighboring areas of the RSFSR and Latvia.

Masherov later became famous as a successful partisan leader nicknamed Dubnyak. His detachment conducted effective operations to destroy German communications, eliminated Wehrmacht soldiers, and grew in numbers. In 1944, Masherov was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. He was only 26 years old at the time. After the war, his career developed successfully along the Komsomol line. The work of a high-ranking official somewhat changed Masherov's image, transforming him from a brave warrior into a worker on the ideological front. His experience as a school teacher, gained even before the war, helped him adapt to his new role.

As before, Masherov could inspire people with his speeches, but now he was surrounded not by partisans in sheepskin coats, but by enthusiastic young men in jackets. The words of the Komsomol leader became less specific, more grandiloquent and propagandistic. Masherov's rise was not hindered even by the fact that his father was repressed as an enemy of the people in 1937.

Of course, the authorities knew about his father's fate, but they did not force him to denounce himself. Later, Masherov entered the ranks of the nomenklatura, that is, the caste of the untouchables who were not checked. Nevertheless, he changed the surname Masher to Masherov by adding the final letter "v." In the order awarding the title of Hero of the Soviet Union to the partisan, he was already listed under this surname.

"The arrest and death of his father were overshadowed by the tragic fate of his mother: she was a partisan, arrested by the Germans and then executed," adds Maksimenko. "Thus, the tragedy of Masherov's fate reflects the entire tragedy of Soviet history."

In 1959, Miron Masherov was rehabilitated by a decision of the Supreme Court of the Belarusian SSR. Pyotr was already part of the leadership of the party organization of the republic; for his paternal feelings, this was a touching moment, the expert believes. The historian has no doubt that the family tragedy influenced the formation of Masherov's personality.

"The man knew his inner truth," notes Maksimenko. "In one of the films, a peasant woman appeared, whose mother was executed along with Masherov's mother. She said that when young Pyotr came to the village and inquired about his mother's fate, he seemed to her 'not like always, a bit frightening.' That is, despite his charming smile, the war changed him."

In 1952, the leader of the Komsomol of Belarus went to Vienna for a nationwide youth rally for peace. The Cold War was gaining strength, and the USSR still did not have a peace treaty with Austria. The representatives of the Soviet delegation were carefully prepared and constantly reminded: in the former center of Nazism, one must be on guard.

The atmosphere was indeed far from serene. Masherov imagined CIA agents everywhere, and if a passerby on the street looked at him too closely, the Komsomol leader, barely moving his lips and not turning his head, would say to his companions: "That's a spy, we’re covering our tracks!"

Every evening, he found anti-Soviet leaflets and even books in his hotel room. He would throw the literature that had been planted outside the door. Masherov never left his shoes in the hallway for cleaning, as other foreigners did — he was convinced that a Soviet person should not humiliate hotel staff with such work, and before going to the next meeting, he carefully cleaned his shoes himself.

The behavior of the 34-year-old Masherov in Vienna paints a portrait of a young official of that time: unpretentious in everyday life, somewhat suspicious, and loyal to communist ideals. There were several such figures on the political Olympus of the Belarusian SSR — with partisan experience behind them and great ambitions.

Mikhail Zimyanyn rose to the position of secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU. Kirill Mazurov's promotion was even more successful. Under early Khrushchev, he was head of the Belarusian government, then the first secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Belarus. In 1965, Brezhnev brought Mazurov to Moscow as the first deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR. The question of who would replace him in Minsk was not even raised.

"Until the collapse of the USSR, there was not a single leader of the republic or member of the Politburo who fought and received the title of Hero of the Soviet Union during the war," notes Maksimenko. Under Masherov's leadership, Belarus experienced significant economic growth. Industry and agriculture developed actively. The national income during his 15 years at the head of the republic increased several times.

"As a leader, he tried very hard," says a Belarusian public figure who witnessed Masherov's time, to Lenta.ru. "In the stores in the 1970s, there was no abundance of goods, as in other parts of the USSR, but the basics could be bought. In Minsk, of course, the selection was richer than in the regions. Masherov tried to develop agriculture as best he could, but the indicators were not very good. Under him, work on land reclamation was very active. He himself did not hesitate to travel to different areas and meet with peasants. He could easily take a scythe in his hands during a visit to some village."

In the view of Karen Brutenets, a candidate for the Central Committee of the CPSU during perestroika, the Soviet leadership of the 1970s was significantly inferior to its predecessors. Under Brezhnev, "all sorts of tricksters" and opportunists rushed to the forefront, and the emergence of new and younger people in the leadership became a difficult task. Only convenient figures could successfully pass the filter — those who already had a patron among the top brass, did not raise concerns with the general secretary and his entourage due to their brightness and independence.

Against this backdrop, Masherov was perhaps an exception to the rules. Therefore, he was not particularly liked in Moscow, where the independence of the Belarusian leader, his desire to change or bypass union decisions, and his unwillingness to praise the leadership and demonstrate loyalty caused irritation.

Especially disliked by the center was Masherov's high popularity in Belarus. The head of the republic was blocked from membership in the Politburo, where, for example, his Ukrainian colleague Vladimir Shcherbitsky sat. The title of Hero of Socialist Labor, which was generously awarded to first secretaries, was given to him last and after a long delay, although Belarus distinguished itself in the 1970s precisely for its economic successes.

"A true, not a fake Hero of the Soviet Union, Masherov favorably distinguished himself from the other members of the Politburo of that period," noted the famous Soviet and Russian lawyer Vladimir Kalinichenko. "A modest and charming man, he enjoyed great respect in Belarus, and indeed in the country as well."

An example of Masherov's demonstrative independence is provided in the memoirs of the translator of Soviet leaders, Viktor Sukhodrev. When U.S. President Richard Nixon visited the USSR in 1974, the first secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Belarus decided to personally take him to Khatyn to inspect the memorial complex, the construction of which he himself had initiated.

"The Politburo's resolution does not provide for this, but I will not ask anyone and will go," Masherov winked at the translator, who knew that according to protocol, a lower-ranking official — the chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of Belarus — was supposed to accompany the high guest on such a trip. By violating protocol, the former partisan displayed rare independence for those times. Brezhnev's entourage, however, preferred not to notice this demarche.

While inspecting the memorial, at one point Nixon separated from the group and was left alone. It was clear that he was touched by the atmosphere. American newspapers at the time wrote that by showing the president Khatyn, the Soviet side was using his visit for propaganda purposes.

"Nixon sees Khatyn, not Katyn," they shouted, hinting at the execution of Polish officers in 1940, which the USSR then refused to acknowledge.

High-ranking officials at that time were driven around in a bulletproof ZIL-4104, popularly nicknamed the "members' car." However, Masherov did not favor the bulky limousine and remained faithful to the lighter (though still over two tons) and less protected "Chaika" GAZ-13. The leader of Belarus disliked pompous outings in a long motorcade, considering such privileges the lot of bourgeois leaders, not of those from the people, to whom he identified himself. He also disliked the flashing lights on the car — another symbol of inequality.

The rules for the passage of a candidate for membership in the Politburo on that fateful day were grossly violated not only at Masherov's whim. According to instructions, traffic police posts were supposed to be along the route of the motorcade; however, there were no police cars when they exited the secondary road onto the highway.

Masherov's "Chaika" was accompanied by two "Volgas" — one was moving ahead, and the other, with special signals, was bringing up the rear. The distance between the cars was 60–70 meters. They were driving at a speed of 100–120 kilometers per hour on the highway, as required by safety regulations: such speed does not allow for precise shooting at cars.

A kilometer before the intersection of the highway with the turnoff to the poultry farm, the leading "Volga," having climbed the rise, began to descend first. Just at that moment, the driver Nikolai Taraykovich, moving in the oncoming lane in a large MAZ, saw the motorcade (his attention was drawn by the flashing lights of the second "Volga") and, as required by the rules, moved to the right and began to slow down; the speed of the truck sharply decreased. Having missed this maneuver, Pustovit at the last moment tried to avoid a collision (although, according to one of the commanders of the Minsk traffic police, Konstantin Andronchik, he intended to turn left — towards the poultry farm).

The driver of the first escort vehicle noticed the dump truck emerging from behind the MAZ but did not sacrifice himself for the big boss; he stepped on the gas and at the last moment narrowly avoided the truck — they were separated by mere meters. The driver of the "Chaika," Yevgeny Zaytsev, began to brake but, orienting himself to the maneuver of the "Volga," suddenly also increased speed, which only added force to the head-on collision.

Later, investigators would have questions for this person: he was already driving Masherov in violation of the rules because he had retired by that time. The first secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Belarus succumbed to persuasion and kept Zaytsev, whom he had known well since partisan times. No one was even disturbed by the fact that the driver had health problems — he suffered from sciatica and had eye disease. According to investigator Kalinichenko, at the critical moment, the elderly driver Zaytsev could not react correctly to Pustovit's actions, who grossly violated traffic rules.

Kalinichenko saw Masherov's corpse in the morgue.

"A torn wound on the forehead, a right leg twisted like a breeches, broken arms," he described in his memoirs. "The modest clothing of such a high-ranking party worker struck me, by my standards."

To determine the degree of responsibility of driver Zaytsev, experienced drivers who had transported influential passengers were interviewed. They noted that since the collision between the dump truck and the "Chaika" occurred practically at the intersection with the secondary road, Zaytsev should have attempted to exit onto it or steer right into the field, where he could have reduced speed. In turn, the forensic and automotive technical examination of the Ministry of Justice of the USSR concluded that the truck driver Nikolai Pustovit had the opportunity to prevent the accident if he had timely reduced speed, while his colleague in the "Chaika" did not.

A few years before the tragedy, Alexei Kosygin found himself in a similar situation in the Minsk region: his driver reacted instantly to the danger and threw the car into a ditch. The car plowed through the potato beds, but the head of the government remained safe and almost unharmed.

In 1980, Brezhnev was seriously ill and was visibly aging. The question of his replacement could not help but be discussed by political factions. However, Masherov, the first secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Belarus, hardly had serious chances to step directly into the top position in the CPSU — there were plenty of more obvious contenders around the general secretary. However, a change at the highest levels was needed not only for Brezhnev.

"There was no talk of Masherov becoming Brezhnev's successor," recalls Dubitsky. "More about his desire for independence and unwillingness to share. I repeat, the issue was the unwillingness to feed other republics that perhaps were not working hard enough themselves. Right now, Russia has risen normally, but I was just struck by the empty gardens in Sverdlovsk when I came there on business. That is, people were not used to managing their agriculture."

Masherov's elder daughter Natalia, a contemporary Belarusian politician and a former presidential candidate in the early 2000s, believes that her father should have become the new prime minister after Kosygin. Work on this appointment was underway during the 1980 Olympics. The long-time head of government was preparing to vacate his post due to deteriorating health.

Masherov was buried on October 7, 1980. Tens of thousands of residents of Minsk walked to the coffin, and no fewer people awaited the procession at the city cemetery. However, of the first secretaries of the regional committees, only the neighbor from Lithuania, Pyatras Grishkavichus, arrived to say goodbye to his colleague. Brezhnev limited himself to sending a funeral wreath. Minsk residents whispered among themselves that their favorite had not found a place in the necropolis by the Kremlin wall, and that Moscow seemed to be trying to bury Masherov as modestly as possible.

Kosygin was replaced on October 23 by Nikolai Tikhonov, and Aliyev soon became his first deputy.

Truck driver Nikolai Pustovit was sentenced to 15 years in prison for violating traffic safety rules that led to the death of several people. He served only five years and was released under an amnesty on the occasion of another anniversary of the establishment of Soviet power. In the 1990s, Pustovit became a fairly successful entrepreneur in the agricultural sector, did not refuse interviews, and always stated that there was no malicious intent in his actions on the road. He considered himself guilty only conditionally, hinting at a greater degree of responsibility for driver Taraykovich than established by the investigation.

"I am often asked whether I sincerely believe in the accidental death of Masherov," Kalinichenko, who passed away in 2022, admitted. "I answer: yes. But a worm of doubt remains. There are super-genius operations by special services, after all."

Historian Maksimenko does not believe that the Belarusian leader was being prepared for the role of Kosygin. In his opinion, Masherov could have been appointed at most to the position of first deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR.

"But his historical role is as the head of the republic," the interlocutor of Lenta.ru develops his thought. "Masherov is a born leader. Had he lived to see perestroika, he could have become the chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. He was ahead of his time. I think he would have given perestroika a somewhat different direction.

Leave a comment