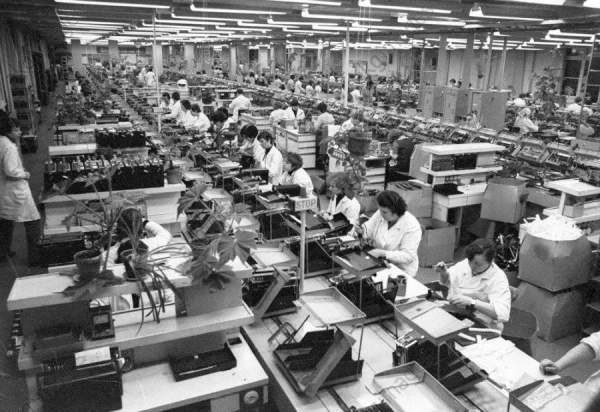

The times of Atmoda (Renaissance) were paradoxical: society clearly aspired to independence, but there was uncertainty in economic matters, stated Gatis Krumiņš, leading researcher at the University of Vidzeme and scientific editor of the book “The History of Latvia’s Economy,” in the podcast tv3.lv “Piķis un ģēvelis!”

Political freedom was perceived as a given — the flag, coat of arms, and the idea of independence united people, but there was no clear answer to the question of “what to do with the economy?” at that time.

Krumiņš emphasizes that it is precisely the legacy of Russification and the limited knowledge of the generation in both languages and the principles of modern economics that have held Latvia back — both mentally and practically.

The researcher provides specific examples: even after the declaration of the restoration of independence, the Industry Commission of the Supreme Council was preparing a new industrial law in Russian, as officials simply did not know how to draft professional documents in Latvian.

According to Krumiņš, this generation — today’s 50+ — still carries the mental trauma of that time: almost everyone received education in the Soviet system, where Western languages and economic knowledge were not needed.

“I remember myself — I was 18 then, I knew one or two words in English. It was not required in school. You see, this generation — my generation 50+ — is now in power. Although we support the Latvian state, I believe this generation is mentally traumatized by all of that,” Krumiņš added.

In his opinion, this has complicated the ability to quickly build an effective market economy, especially compared to the situation after World War I, when Latvian society was much more closely connected to the European civilizational space.