The main external difference from monkeys was established about 25 million years ago.

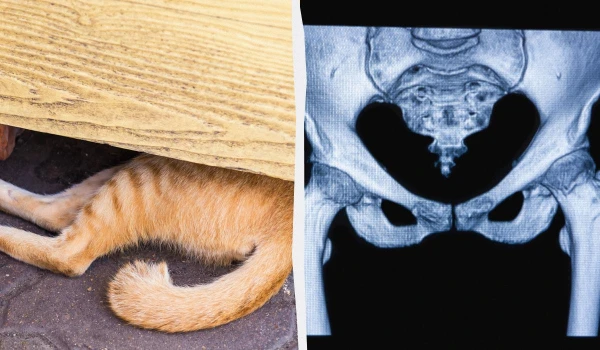

There is a question that every child has probably asked at some point: why don’t we have tails? Our pets do. In fact, most vertebrates have them, and at least externally, some invertebrates do too.

We even sometimes euphemistically refer to our own "tails" or endure the agony of a bruised coccyx — all without ever enjoying a real appendage or even a decorative limb for our suffering, writes IFL Science. But why don’t we have a tail?

Of course, technically humans do have them. Only for a short period, though. During the 5th and 6th weeks of gestation, a human embryo has a tail with 10–12 vertebrae. By the 8th week, the human tail disappears, as noted in a scientific report.

Thus, except for extremely rare cases, humans are born without tails — and even when we do come into the world with a tail, it is almost never a true tail: it usually lacks bones, and the owner cannot move it; it is merely an "abnormal elongation of the coccygeal vertebrae," the report also states.

Why Humans Lost Their Tails

After all, tails are ubiquitous in the animal kingdom. They help cats maintain balance and allow monkeys to climb and swing through trees. Tails are useful for communication — think of a dog wagging its tail or the warning rattle of a rattlesnake. In extreme cases, they can be discarded to distract a predator. So why did we need to get rid of them?

The History of the Tail

The last time our species generally had tails was about 25 million years ago, before the split between the branches of great apes and Old World monkeys. The latter retained their fifth limbs; we — along with other great apes like gorillas, chimpanzees, orangutans, and bonobos — did not.

"None of us great apes have tails," confirmed zoologist David Yang, author of The Discovery of Evolution and director of the Tigs Museum at the University of Melbourne, in 2016. But we are not the only ones with this distinction: "Small apes, such as gibbons, also lack tails," Yang pointed out, "and they give us a clue about how the absence of a tail can be advantageous."

"Gibbons are able to use their long arms to swing from branch to branch in the canopies of Southeast Asian forests. When they swing, their torso and legs hang down, giving their body a vertical posture. A tail would only get in the way and be a hindrance in this type of movement," Yang once stated.

For this obvious reason, the absence of tails in us is often linked to our bipedality. Having a tail would not be particularly useful for an upright bipedal creature specialized in long-distance hunting on the ground — and thus, it is believed we got rid of them. However, as logical as this explanation sounds, the opposite happened. The tail disappeared first.

As it turns out, the key to the mystery lies not in what humans lack, but in what other animals have. In other species, tail formation begins at an early stage of fetal development: the future body plan of the animal is determined by so-called Hox genes, which start to work when the organism becomes complex enough to have an inside and an outside.

Part of the job of these genes is to determine the structure of the spine — and for many animals, this includes a tail. After the initial impulse from the Hox genes, whole sets of other genes come into play: some code for a long and thin tail; others — for a fluffy and furry one; still others — for one that can easily fall off if necessary. To be honest, we are still far from fully understanding which gene is responsible for what specifically — but this is where the reason for our own tail's absence should lie.

Therefore, scientists compared the DNA of six species of tailless monkeys with nine species of tailed monkeys — and found something no one expected. "It was like a lightning strike," said Jeff Boak, director of the Langone Medical Center's Institute of Systematic Genetics at New York University and the senior author of the study.

"It was non-coding DNA," he explained — sequences that were "100 percent conserved in all monkeys and 100 percent absent in all Old World monkeys."

Genetic 'Junk'

The genes that led to the loss of the tail in humans are a small fragment of DNA — a so-called Alu element. Such elements are found throughout our genome. Until about five years ago, they were considered useless — a kind of "genetic junk" that no longer plays a role for our species.

But Alu elements also belong to the class of so-called "jumping" genes: they can move around the genome, causing mutations as they go. Apparently, at some point in the distant past, one Alu element ended up in the TBXT gene, which controls tail length — and once it was there, it began to behave incorrectly.

Scientists even proved this. The team inserted an Alu element into tail genes in mice, and the result was instantaneous: the tail disappeared.

Leave a comment